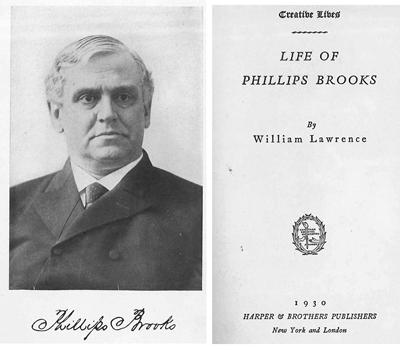

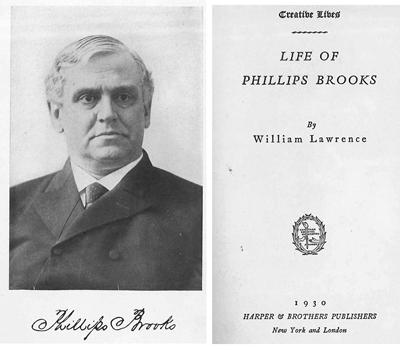

St. George’s received this book donated by Rev. Richard Carbaugh of Christ Lutheran Church. The author William Lawrence (1850–1941) was elected as the 7th Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts (1893–1927) and wrote this after retiring from this position. His sons, following in his footsteps also became bishops of the Episcopal Church. William Appleton Lawrence was elected 3rd Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Westernrn Massachusetts (1925–41) and Frederic C. Lawrence was elected suffragan bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts (1956–68).

Lawrence wrote about Brooks on the 10th anniversary of his death in 1903 – “To many of you present in this church, which is so associated with him, his personal presence is vivid. His majestic figure in this pulpit, the action of his body, the tones of his voice, the animation of his face, and the glow of his imagery all come back as if it were yesterday… ”

“The truth of the Incarnation was the central truth of his life, thought, and preaching. For him it solved the pressing problems of life and nature, and knit the universe, God, and his creation into living unity.

“It was this fundamental truth, bound up as it is in the fact of the divine sonship of man, that led him to his belief in the value of the human soul, which, you remember, marked the climax of his Lectures on Preaching. With the movement of science the individual was losing his value. Phillips Brooks threw himself just then into that breach with all his power, and affirmed the essential value of the individual. This gave him the evangelical element in his message; this emphasized the direct responsibility of each soul to God, and enabled him while preaching to the larger world to bring his words home to the conscience and aspirations of each man, woman, and child within sound of his voice.

“It was this, too, that made him a source of inspiration to all workers in the uplifting of the down-trodden. He had very little interest in preaching upon the methods and work of social service, deeply as he was interested in those who were carrying them out. His mission was to reach the deeper motives and strike the springs of enthusiasm, not so much £or humanity in the abstract as for men, God’s children; and through his preaching the springs gushed forth.”

These pages describe when he came to St. George’s.

Related – Phillips Brooks at St. George’s

JUNE 30, 1859, was Commencement Day at Alexandria. Brooks read his thesis on “The Centralizing Power of The Gospel” to a large audience which included his father. The next day Brooks and several of his classmates were ordained deacons and on the day following he went to pass Sunday with his friend, the Rev. Alfred M. Randolph, Rector at Fredericksburg, and to preach for him.

Can we conjure up the scene on Sunday? – a typical Virginia city with Colonial houses, shade trees and clouds of dust j the July sun poured down its heat upon the good people wending their way to St. George’s Church, whose rector was so beloved throughout the state that he became later, and was for many years, Bishop of Southern Virginia. He was a quaint, scholarly and absent-minded man. The gentlefolk approaching the church greeted their neighbors. The ladies closed their parasols, the men dusted their boots and all entered the quiet and simple church. Behind were the poor whites and in the gallery a few negroes. It was the Old South before the War. The preacher, however, was a young giant from the radical town of Boston, and he a radical too: a hater of the sin of slavery. Only five months later in a town not far distant John Brown was hung, and three and one half years later Fredericksburg was wrecked by the guns of North and South, and her streets and river stained with the blood of the youth of Boston. It was the day before the fourth of July, and a Massachusetts man was speaking to Virginians. We have no record of what he said, but years later Bishop Randolph described the impression made. “In thinking of my impression of Brooks’s two first sermons and of the way they were spoken, and also of the impression made upon the many intelligent people who listened to him, I am reminded of these characteristics of his preaching which all who ever heard him will recognize,—a singular absence of self-consciousness, a spontaneity of beautiful thinking, clothed in pure English words, a joy in his own thoughts, and a victorious mastery of the truth he was telling, combined with humility and reverence and love for the congregation. I have heard him often since, and the impression is always the same. He was unspoiled and unspotted by the world, especially by that most dangerous and insidious of all the world forces, the praise of men.”