We have looked at the design of the pews in part 2 and now we turn to how the pews contributed financially to the Church. The pews paid for the 1849 Church and until the 1920’s generally contributed at least 4% of more of revenue back to the Church per year.

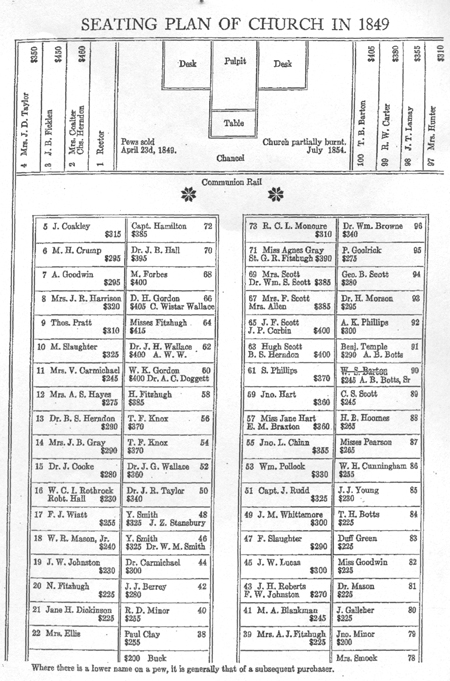

The illustration above shows the result of the pew sale in 1849 and was pasted in the 1865-1906 Vestry book and later incorporated in Quenzel’s history of St. George’s. Another version was recently discovered at the Heritage Center. This was printed by J. (Jesse) White, Printer Town Hall, Fred’g and is undated. There are over 25 differences in names, 6 differences in prices (50% lower, 50% higher). Since so many pew prices are not listed, this may be a “pre-sale document”. A discount was available if you held a pew in the previous or second church.

Transfer was noted in the “record book” with the funds probably deposited at the National Bank of Fredericksburg. Deeds are mentioned in the Vestry minutes though no evidence of actual deeds has been found.

80 pews were purchased for $24,331 the day after the consecration of the Church. The remainder would be “free pews” open to “strangers”. This is equivalent to approximately $500,000 in 2008 dollars. Church historian Quenzel describes the sale “exciting and entertaining”, practically “everyone was there” and pews went like “hot cakes”. Two prices are unknown. Pews closest to the front cost more and were likely to be purchased by those with means. It fit in with a Christian perception of social rank as part of a divinely ordered hierarchy of creation. The highest price pew #2 was purchased by the Mrs. Coalter for $460 ($10,000 to $12,000 in 2008 dollars). The lowest price of $200 was Pew 79 purchased by John Minor. Eliminating the two unknown prices the average was $312. Numbering of pews was important for record keeping.

As time went on pews in Churches were set aside as general seating for special groups, the poor, widows, the hard-of-hearing, and black people. In 1878, the Vestry noted that an entire block of seats in extreme end of south gallery would be “set apart for the colored people. “ Note it said seats and not pews though there were pews there by 1906. Also, in 1878 the Vestry declared the Rector could declare pews “free” by notice from the chancel for a series of meetings.

The pew tax arose shortly after the Civil War as part of the plan to get the Church back on its feet financially.

The Committee for the Repairs of the Church was given power in1866 to both rent pews and charge pew tax up to $20. In the next year they levied 8% tax on the original cost of the pews. Thus, in the first year they collected $977 from the pews out of total income of $1945. The Church at the time had expenses of $489 to repair the steeple, repair the wall and repairs to the furnace and gas. Another $1,000 was needed for expenses in 1868. By 1869 $5 would be instituted for covering “parochial expenses” – rector salary, sexton hire, fuel, lights, insurance, repairs (As an aside the envelope system to place donations arose at the same time to encourage weekly contributions). The pew tax was collected from Easter to Easter since the Vestry had their annual meeting at that time. Both pews and envelope system led the Vestry in 1870 to declare the Church “in the best shape since the war.”

The pew tax became a victim of its early success. By 1880 arrearages were developing and by the next year as finances tightened in the Church, the treasurer was asked address a circular letter to everyone indebted for pew tax to meet demands of “contingent expenses”. If the tax was not paid the pews would revert back to the Church. By 1884, they were “naming names” in the Vestry minutes. Mrs. Jane Goolrick in pew 96 had not paid a pew tax for 14 years! They wrote letters encouraging the delinquent holders to allow the Church to rent out the pews by a certain date. Sometimes it took personal intervention. In late 1924 a committee went to see William Bond “regarding unpaid pew taxes reported. After conferring with Bond he had paid up all arrearages.” However, there were exceptions made to paying the tax. An exception was made for Dr. J. Thompson for services as registrar of the Vestry.

Pew taxes had to be paid by estates. In 1899, $25 in delinquent taxes for pew 100 had accumulated on the Estate of William S. Barton. The estate was told to “rent out to the same party until this is paid.”

By 20th century the system was re-evaluated. A committee under Judge Embrey, Judge Chichester and E. J. Smith was appointed by the Vestry to review the pew ownership system. No resulting report was found. The following chart shows the trend of pew tax collections:

|

Year |

Pew Tax |

Total Income |

% income |

|

1885 |

404 |

3,160 |

13% |

|

1889 |

313 |

2,916 |

11% |

|

1896 |

289 |

3,151 |

9% |

|

1908 |

205 |

3,654 |

6% |

|

1909 |

500 |

4,218 |

12% |

|

1910 |

155 |

3,727 |

4% |

|

1921 |

320 |

10,691 |

3% |

|

1922 |

310 |

8,314 |

4% |

|

1925 |

297 |

7,231 |

4% |

|

1930 |

210 |

10,595 |

2% |

|

1932 |

193 |

8,691 |

2% |

|

1933 |

138 |

7,245 |

2% |

|

1941 |

78 |

8,284 |

1% |

The tax was abolished by Vestry April 5, 1943, retroactive to Jan 1, 1943. There was no discussion – it was simply done. No discussions were recorded in the minutes in the years just prior to 1943. The pew tax had run its course – it was contributing little financially to the Church and was probably more trouble to try to collect. In the years before, only half of the pews were owned (46 of 92 available). 17 of the 46 were estates. This contrasts with just under 63% of the pews owned in 1907.

One of the problems is that the original pew tax amount of $5 in 1869 was never increased over time. Other sources of revenue, such as trust revenue also emerged. But there was a larger issue at hand. America had changed since it was inaugurated in the 19th century. By World War II, families were on the move – no longer staying in one community. Class structure was more fluid and cooperation was a predominant theme with the war.

Despite the passage of time, many people today still retain a concept of the pew they sit in as “my pew.” even though all pews at St. George’s are now “free pews.”