Douglas Hamilton Knox, Jr. was the third and last child of Douglas Hamilton Knox and Loula Brockenbrough Knox, born in 1896 in Fredericksburg, Virginia. His family had been established in the area since colonial times, with a long tradition of active involvement in civic affairs, local industry, and St. George’s. The family had served on the Vestry, led Christian education and the sons participated in youth activities. This is primarily the story of the later Knoxes, Douglas, Jr and Thomas III who came of age in the early 20th century. The letters they wrote provide a rich legacy of that family.

The Knoxes were an exceptionally close-knit family, with all seven of patriarch Thomas F. Knox Jr.’s adult children and their families living with their parents at one time or another in their large brick home at 1200 Princess Anne Street, today the Kenmore Inn.

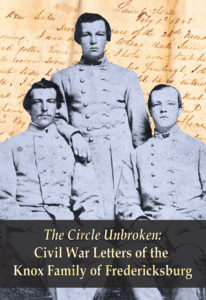

The family had been tested in the Civil War with six sons going off to war and fortunately all returning. And they wrote letters – and they were preserved! This distinguished them from other families of the time. The 117 Civil War letters have been published in 1913 as The Circle Unbroken: Civil War Letters of the Knox Family of Fredericksburg by the combined staff of the Central Rappahannock Heritage Center, Inc and The Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc. The preservation of the letters by Douglas Knox’s daughter Lucy and then to her niece Elizabeth Knox Gray and finally at her death in 2006 to her daughter Lucy Brockenbrough Gray sets them apart from other families at the time.

This article explores the later letters primarily from 1913-1918 through both Douglas and Thomas as the boys grew into manhood.

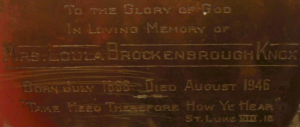

50 Years after the Civil War the family was challenged again. Their mother, Loula Brockenbrough Knox had to endure the loss of her husband in 1914, Douglas and Tom’s uncle Robert T. Knox in 1915 and two sons Douglas in 1918 at age 22 and Thomas in 1919 at 30. It is appropriate that Lucy S. (Brockenbrough) Knox eventually had four St. George’s pews (40,41,54,55) with her name plate to remember her and her losses within five years. Finally the circle unbroken in the Civil War was broken by these events.

The Knox family life began in Fredericksburg in the early 19th century at the time of St. George’s 2nd church (1815-1849). Douglas’ grandfather Thomas F. Knox, Sr. (1807-1890) was from Culpeper and came to Fredericksburg in 1821 to work with his uncle William A. Knox and became a “wheat speculator and flour manufacturer” according to Quinn’s history of Fredericksburg.

Knox, like many of his generation, was more of a general merchant and businessman. He was a grocer in 1830, Steam line agent in 1834 and Silk company agent in 1836. By the 1850’s he was busy as a director of several companies: Fredericksburg Insurance Company, the Canal Company, the Water Power Company and the Bank of Commerce. He retired from business during the Civil War years. That allowed him more time to serve St. George’s.

He first was elected to the Vestry in 1836 and served until his death in 1890. That’s 54 years, that’s almost impossible due Vestry term limits. He purchased pew 56 at the current church in 1849 and served on the building committee that directed its construction. He was secretary of the Vestry 1854 and wrote a letter July 29, 1854 after the fire in the chancel expressing thanks to the fire company and citizens for helping put out St. George’s fire. He was senior warden from 1874 until his death.

Knox was a significant landowner. With 14 children they needed a large dwelling. In 1857, he purchased what is today the Kenmore Inn, 1200 Princess Anne Street, Lot 95 and is known as the Knox House. He bought that property from another St. Georgian, Alexander K. Phillips who helped to establish the National Bank toward the end of the Civil War.

While all his sons fortunately returned from the war, it was an economic disaster for the family. In 1860, Thomas Knox owned $50,000 worth of real estate and $22,000 of personal property (much of that surely slaves). But by the time the census taker came around in 1870, that $72,000 fortune had shrunk to just $8,000, including just $500 of personal property.

Census records, city directories, and their correspondence to each other detail their comings and goings from the old Knox home from its purchase in 1857 until it was sold in 1911.

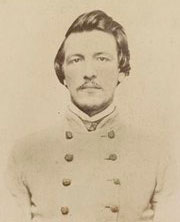

The next generation continued in Fredericksburg and worshipped at St. George’s though struggled economically. One of his children was Douglas Knox, Sr. (1847-1919) who married Loula S. Brockenbrough.

Knox was a student at VMI and served in the Civil War. Afterwards he had been journeyed to Cedar Rapids Iowa until 1876.

Knox was a grocer. He was a member of firm Brokenborough & Knox on Commerce St. in 1876 and later a firm in his name by 1881.

In 1882, an advertisement in a local paper described his stock. “A very good stock of groceries, canned goods, pickles, sauces, crakers, cakes, nuts and many other good things too numerous to mention are kept constantly on hand.”

A biography of his business in the Fredericksburg Star 1890 stated. “His is known far and near and his store is stocked with groceries of all kinds, fancy and staple” and was considered one of the largest grocers. “He gives his business close and careful personal attention and it is very certain that he will not be left in the race for success.”

At St. George’s Knox was known as a Christian education teacher. He taught Sunday school longer than any other male teacher under Marshall Hall’s who served a superintendent of the Sunday school for 25 years. It expanded from 75 to 200 was in “flourishing condition.”

Douglas Knox also served on the Vestry beginning in 1884, became the treasurer and only retired when his health worsened. He and his wife produced three children Lucy B. Knox, Douglas F. Knox Jr. and Thomas F. Knox Jr growing up at the turn of the century.

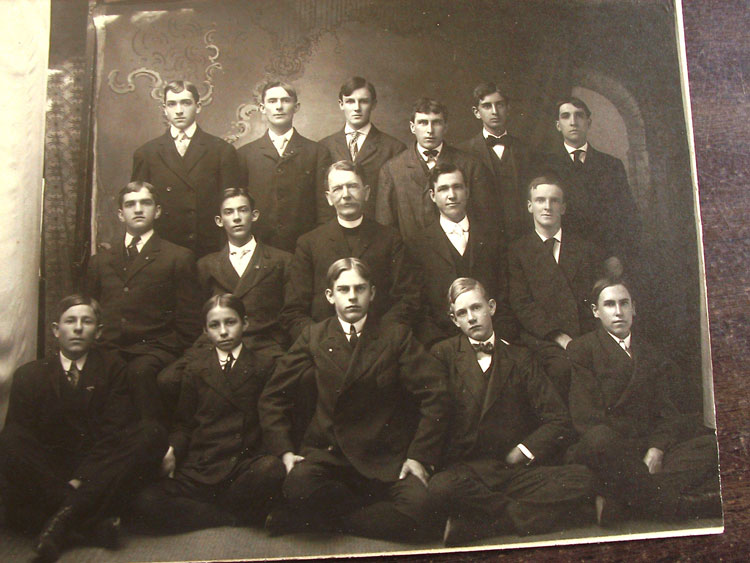

Thomas was the oldest, born in 1888 and Douglas younger by 8 years, born in 1896. Both attended local schools, including the Hanover School. A picture was taken in front of St. George’s in 1902 and may be the earliest picture of the “big red doors.” Thomas Knox attended there 2 years, top right, along with his brother Douglas, bottom left.

Thomas was also a member of the Junior Brotherhood of St. Andrew from at least 1905 to 1907 which met at St. George’s. A generous parishioner donated the records to us in 2012. The chapter was chartered on November 11, 1898 with Rev. W. D. Smith and five boys. This was both an evangelistic and outreach group.

The 1905 report was specific as to their mission. “The purpose of our Society is to ask all who do not attend any church at all to come to our services; to act as ushers and to be on hand to welcome strangers.” There were two rules – the rule of prayer and service. “The rule of prayer is to pray daily for the spread of Christ’s kingdom among boys. The rule is to take some part in the work, worship or study of the church and to try each week to bring other boys to do the same.” Their maximum membership was 25 but they lost 11 to college or work. The membership in 1905 was 14 with an average attendance of 10. They also tracked which of their members attended church which was considered part of their activities.

“Hotel work” was an important of their work and was included in their 1906 report. “Two of us go to the hotel both morning and night to extend a personal invitation to men who may be there and bring them to our services. We have averaged one person a Sunday in the past year…” They never listed the hotels visited in Fredericksburg. However, at the time of the society there were five hotels in operation within 5 blocks of the Church.

A record in the back of the journal listed 29 people brought to the church over the period. They posted cards with the times of the service at the hotel and added one in the Narthex.

Tom would gravitate toward mechanical drawing and engineering. After spending two years at the Hanover School, he spent two years at the McGrath School of Mathematics for “physics and higher mathematics” and then 3 ½ years at International correspondence schools (mechanical engineering). Fromom 1906-1908 he studied in Winston-Salem, NC at Twin City Business College (applied mathematics) and then at the Morris Scientific Engineering Institute (mechanical engineering).

He lists his early career steps to establish his career:

Aug., 1908-Sept., 1909 – he created his own business in Washington, DC McGill Building 9th and G. Street – “I designed and worked out details of fire-arms, tool machines, refining machinery , etc.”

Sept, 1909- July,1911– worked as a specialist in “developing various mechanical devices to be patented by inventors through Victor J. Evans & Co., 9th and Grant Sts. Washington”. He added that he developed “a fair knowledge of patent law” which he found was valuable in his work.

Douglas was born when his father was forty-nine years old, a prematurely aging man who whose health was rapidly failing. By 1911 when Douglas was fifteen, Douglas Senior was too infirm to manage his once-successful grocery business, and was barely able to support his family by working as a shipping clerk. Like many Fredericksburg families in the hard years after the Civil War, the Knoxes took in boarders for extra income as they rented a succession of large frame houses on Fauquier and Prince Edward Streets.

This was only one of the industrial locations of the Knox brothers in Fredericksburg.

The genesis of the R. T. Knox operation was a grist mill created by Thomas F. Knox, Sr on the lower raceway in present-day Old Mill Park on Caroline St near Bridgewater St. These mills ground various grades of flour, meal and animal feeds on toll and for wholesale and retail distribution.

In 1867, Robert T. Knox and his brother converted this to a sumac and bone mill. The plant actually had three mills, two for processing sumac and one for grinding bone dust, used in making fertilizer. In 1884, the factory had the capacity for producing about 1,000 tons of sumac per year. It was also manufacturing fertilizer, which was sold to local farmers. The sumac was either ground, to be used in the process of tanning leather, or extracted as a liquid, used in dyeing textiles.

During the summer of 1913, Douglas labored in the torrid heat of Caroline County, helping his older brother Tom supervise the construction of a new sumac extract plant at Milford.

Tom reported during this time on his resume – July 1911- Oct., 1915 – “reorganized the business of Messrs. R. T. Knox and Bros (Established 1866) of Fredericksburg, VA, manufacturers of dye and tanning materials.” “I designed and built, with day labor, a new factory with a capacity of two thousand barrels of materials per annum, and became half partner in the business and remained there as Manager until the firm changed hands.” (His uncle R. T. Knox, the founder, died at that time in March, 1915.)

The brothers camped in an old canvas tent on the factory premises, bathed in a nearby creek and cooked bread and cabbage on a camp stove for supper, supplemented with an occasional meadowlark shot by Douglas. Periodically, they would take turns going home to Fredericksburg by hopping the RF & P train that ran behind the new factory to check on their ailing father and to report to Uncle Robert on their progress.

Tom’s life did have a bright spot – his love for Elizabeth Rust Pendleton who lived in Washington with her family and were involved in real estate and lived in Colonial Beach at times during the year. She would work in their office. “Little Woman you have just fueled my whole life with sunshine that never existed before” He called her “my precious girl” and himself “your boy.”

On Independence day 1913, he wrote “I will try and fix it so both of us can be at our home in July and dear I will think of you when I go to the Lord’s Communion Table.”

“Little girl I have not quite learned to say my prayers in the spirit that I did when I was younger. I’m trying harder each day. Why is it that I can’t back? I thank God for what he has already done and I will soon be like I used to be. It isn’t that I don’t believe in God but I just can’t express it.”

In the fall of 1913 both Douglas and his Uncle Robert boarded in Milford with his brother Tom and new bride Elizabeth (November, 1913) in a tiny cottage on the factory premises. The sumac extract plant did well enough its first season (sumac leaves were collected in early fall and shipped by rail to Milford for processing), with orders for extract coming in from tanneries all over the United States, Canada, and Europe.

In March 1914, Douglas H. Knox Senior died at age 67 of “locomotor ataxia,” leaving his wife Loula (47), son Thomas Fitzhugh III (25), daughter Lucy Brockenbrough (23), and Douglas Junior (17).

Douglas apparently continued to work with his brother Tom during the second sumac season (1914) in Milford, but in March 1915, his Uncle Robert died at age 78. The factory was sold and Douglas returned to Fredericksburg. Following his Uncle Robert’s funeral he decided to head west, ending up in Helena, Arkansas. He left his collection of Civil War memorabilia with his brother Tom for safekeeping which he noted in one of the letters.

He stayed in Helena long enough to have personal stationery printed, but apparently returned to Fredericksburg within a few months. Doubtless, he felt responsible for helping his widowed mother and older sister Lucy, who were renting rooms to boarders at 611 Fauquier Street. Adding to Douglas’s concern for his mother was the fact that by now she was completely deaf from an unknown cause.

During this period of financial strain following the loss of the Milford sumac plant, Tom’s wife Elizabeth and baby Sophie were forced to live at her parents’ farm in Colonial Beach while Tom and Douglas stayed in Fredericksburg, desperately trying to earn money. For a while, they acted as sumac brokers for the plant in Milford, sold chickens and cut wood.

In October 1915 the two brothers managed to find a more reliable income source by working as shop assistants at the duPont plant in Hopewell during the 1915-16 winter.

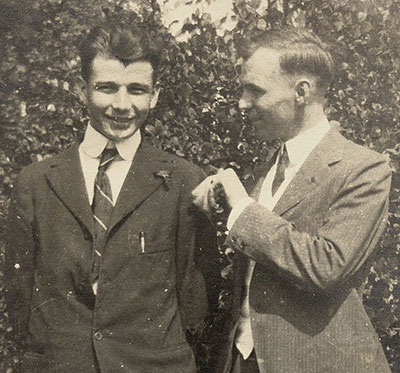

Correspondence between Tom and Elizabeth at this time mentions the chronic lack of funds but also relates the small pleasure of a Christmas gift of fresh fruit from more prosperous relatives in Washington, as well as the pain of their separation. By the summer of 1916 their financial straits eased a bit and the entire family reunited briefly in Fredericksburg, taking time out for a picnic at Federal Hill on Hanover Street, the home of old family friends and taking photographs.

Tom in Jan., 1917 had accepted a civil service appointment and was assigned to the Field Artillery Section of the Ordinance Office in Washington. “I was enabled to gather a thorough knowledge of all details connected with gun carriage construction.”

By fall 1917, Douglas had amassed about a hundred dollars to attend college, matriculating at North Carolina State College in Raleigh. However, as the new year approached, he doubted whether he could continue much longer in school because of the draft which had begun in May, 1917.

Financial issues also were a limiting factor. Tom was sending him money for board. “You can put off sending my Dec Board until the 15th, if you like which will be $14 including my laundry” “Mother will have to paid that $25 before Xmas and I will have to have some doe to go home out.”

On Dec. 22, he received a check from Tom. Received $15 check .. “it caught me in almost a spasm cause I didn’t have any money to pay my board with or to buy my ticket last Wed. AM”

Douglas was resourceful. “You want to know what I have been doing without enough money…” “I have making the best of it – selling some clothes once in a while or doing leggings for the fellows. ” I got on the good side of a Textile Dye fellow and he fournished me with the dye for a 20% profit. So all it cost me was the time, soap and water to wash my hands. I dyed about 35 pair at 15 cents and cleared 4.00 in 2 weeks. I put a sign on my door and I couldn’t fill the orders fast enough nor did I have time for more during final exams”

Family connections were always important. Tom was under financial strains also. “Tom you know that I know your situation .. and that you need not make any excuses to me as they are not necessary… “Mother and Sis not being while to visit you this Xmas and especially I wish that your Elizabeth and all could come and help us enjoy our Christmas.” Lucy Knox was supporting their mother.

He kept his spirits high and kept a practical frame of reference. “I am happy as a lark and so are Lucy and Mother therefore why should I be sad if Fredericksburg is as gloomy as claimed.” “It is best to adopt oneself to the conditions after all than to sit and mope wishing that conditions were better.”

At points he could get frustrated. “I don’t wish anybody any bad luck but I just wish someone would die and leave me and you all a nice legacy of a couple of hundred thousand dollars.”

He already decided to transfer. “If I go back to college as everyone advises me I will not go to N.C. state again but I shall go to Clemson (Military) Agriculture School the 1st of Jan if I can get in there , the college is at Clemson, SC.” He apparently had decided on a military career.

He delighted in meeting another student G. D. Palmer Junior Chemist at Clemson. In mid January, 1918, he wrote “He was so nice to me and insisted upon my going back to Clemson C. with him – so- you see off we went. Clemson doesn’t open until the 15th on account of coal shortage.”

“We put up at the College Hotel at 75¢ per day. We loafed about there for 2 days and were most bored to death with nothing to do. He said, ‘let’s go to the Mt’s on a little hunting expedition, we can have a dandy time.’ So – I up and went off with him. I dressed up in my hunting shoes army pants and shirt ready for a hunt. We rode the Southern for 10 miles and hopped off for a walk of 5 miles, where they raise the finest cotton in the South. This land sells for from 60 to 100 per acre. We stopped at an old farmers house for the night, as he insisted, hunted his place the next day with his dogs, his shells and guns. The sun went down on us next at another place about 3 miles distant where we danced all night and hunted the following day with his boys etc.”

In January 1918, Douglas realized that in fact he would be drafted shortly. He joined the Marines in Richmond in mid-January and headed to Parris Island, South Carolina. “I went down to Richmond Sat to see about joining the marines sometime this week as I believe it is the best branch of the service.”

Tom claimed deferment in June, 1917 since his wife and two children were dependent on his labor. This was the first registration under the Selective Service Act of 1917 for men between the ages of 21 and 30. He was classified as Class IV – “exempted due to extreme hardship- married registrants with dependent spouse or dependent children with insufficient family income if drafted.”

That spring, Douglas completed his training at Parris Island. In an undated letter he wrote, “I surely will be glad to when we leave this camp for the main barracks because there is nothing here but hard work and no play.”

In Feb., he wrote about South Carolina. “The weather down here is wonderful, just like fall weather. Quite warm in the daytime and cool damp nights. Huge palms everywhere and the old Atlantic within 2 miles. The work is the hardest- (I mean the drill) work I ever did but it is making a man out of me. We run about a mile every morning at 5 a.m. Sunday and all with overcoats on too, we have been doing this ever since I enlisted.”

“I am proud to be in the best Company on the Island. We arrived in the camp last Friday evening 3 a.m. on foot from a hike of seven miles with all equipment on our backs nearly 100 lb. It most killed me while I was doing it and I most ground my teeth off but after it was over I didn’t feel sore at all the next day. It was hot that day too, but the Sargeant was proud when he told us not a man fell out, and the other 2 Co’s (93 & 94) that came over 2 days before had 27 men to fall out, because they hadn’t had enough training Just think of it all old top I am the lightest man for my height in any Company on the Island and that is the truth. I am 20 lbs. underweight. My feet remain pretty tender but they are getting better every day.”

“Say old scout we have to do quite a bit of studying out of our Privates Manual too, not easy by any means.”

On another day – “We had double time this morning at 5 a.m. as usual for one mile. the drill today was harder than ever as we drilled for 10 hrs. straight , 45 minutes for dinner. We also had drill for one hour after supper. I am most dead and so are all the other fellows.

Douglas was an expert marksman and was a member of a company that made the highest average of any company that preceded it. In March, he wrote “average because we have only shot in practice and I have averaged 85% so far, which is Expert Rifleman $5.00 extra pay too. If I can only do that good next Wed. Record Day I will be one happy Marine.”

Douglas frequently wrote to his mother and siblings about everyday occurrences: missing home, military training, and hopes for the future.

He was sent to Quantico, Virginia. A letter from April 21 to Tom said that he had reunited with his mother and sister. “I called up Mother & Lucy at F’b’g and they came over here 5:10 P.M. Saturday and we ate supper at the Y.M.C.A. Hostess House and had a very pleasant evening assisted by the Marine Band.”

He was concerned not only about his finances but also his mother’s situation. “Tom I want you to pay what you owe me to Mother in her name at the Planter’s Nat’l Bank. My books show a bal. due of $120.00. The interest can be paid when you are better off. I also want you to start payment as soon as you can and until it is all paid, because she needs the money now.”

Douglas was sent to France in May 1918. His last letter to his brother Tom was written May 29, 1918 while in France.

Douglas was in grand spirits. “It seems ages since I left dear old U.S.A. We have been to so many places that I expect to get a bunch of mail when we settle down. Believe me we are surely getting some good training hiking up and down these mountains. It is the prettiest part of France up here among these hills. This should be a great country for stock raising because I have never seen such a green country before.. We are getting the best training that can be had over here….We are just itching for a chance to go over the top at Fritz.”

On June 14, 1918, he was wounded in the Battle of Belleau Wood. First he was taken to a field hospital, he was transferred to Red Cross Hospital No. 1 in Paris, where he died June 18 at the age of 22.

Knox became the first man from Fredericksburg killed in WWI. The Fredericksburg VA American Legion Post 55 was later name for some of those who fell in that war – Bowen, Franklin Knox

Loula Knox first received the news of Douglas’s death and burial in France via a typewritten letter dated June 29 from The American Red Cross Women’s Relief Corps in France, signed by “A.L. Strong” for the Home Communication Service. Loula immediately wrote to Tom, who was now working in ordnance for the War Department in Washington, enclosing the Red Cross letter.

On August 9th, Loula printed a notice in the Fredericksburg Daily Star that Douglas had been killed in action, quoting details from the Red Cross letters about his death and funeral. She clipped the newspaper obituary for son Tom in Washington, writing at the top, ” I had this printed to give comfort to ‘mutters’ having sons in France.” By a horrible coincidence, in that same Daily Star issue was an article about German sympathizers pretending to be Red Cross representatives sending letters to American families, reporting their loved ones as missing or dead.

From the existing Knox correspondence it is obvious that the clipping about the Hun impostors unleashed a wave of fresh hope that Douglas actually might be alive. Until now all they had they had been told was that he had been brought in from the battlefield unconscious, was without identification and had died the next day.

There had been no notification other than the two letters to Loula in July from A.L. Strong.

Hope for Douglas remained high over the next several days as Tom and others tried desperately to get verification from government authorities. Lucy took a leave from her job and accompanied Loula almost daily by train from Washington to Fredericksburg and back.

Soon Loula found the suspense unbearable, so she placed her valuables in her bank vault, left her boarders and went to stay at her sister Mary Nevitt’s farm near Lorton, to be closer to Tom while she and Lucy waited for news. On August 16, Loula’s nephew Houston K. Sweetser in Fredericksburg sent Tom a letter with the depressing information that both Loula and her sister-in-law Mary Knox Moncure had received in the mail a packet of letters sent to Douglas in May and June, marked as undeliverable.

As late as August 23 there was still no official reply to their inquiries to the Red Cross office, the Marine Corps, and the US government. Loula was determined to stay positive, for her family’s benefit as well as her own.

She wrote Tom that day and called on her knowledge of scripture. “I am sure that the U.S. Gov. will get it to us almost as soon & I do think it wiser to wait, for the report is obliged to come sooner or later- the truth. It is very hard on you to be kept so anxious and I know your great love for me as well as Douglas adds to your grief, but dear child when we are “all to pieces” we have His own statement to comfort us. “My peace I leave with you” “Not as the world giveth” “Let not your heart be troubled neither let it be afraid.”

“I feel like I would give a lot to put my head on your shoulder but my precious, your prayers are comforting and your love and thought keeps me up all day long. I can keep up & do a “whole lot” of things & be glad & “smile” & that helps. We have so much to praise and none to blame. Dear Lucy is doing her best to make good and writes me letters as sweet as yours- she will come to me here on Sat. Eve & stay Sunday.”

Then she wrote in an undated letter-“ I am glad we let our “soldier” go without a word of regret – He was good and true and God’s need of him will be our comfort. I am keeping up for Lucy & you, but so shocked. I want you so if only for an hour – Grace is given me but I cling more to my nearest & dearest as I get older and love more.”

Of course, in the end Douglas’s death was confirmed, although any final acknowledgment from the government is missing from Loula’s save collection of keepsakes and correspondence pertaining to her second son.

On September 29 1918, his name appeared in a Washington DC newspaper on a list of Marine Corps casualties. Afterwards, Loula returned to Fredericksburg and her boarders. Knox received a death benefit of $57.50 were made to Mrs. Know from June 19, 1918 to June 19, 1938 and then $45 a month beginning July 25, 1938.

That October in Roslyn, she welcomed her third grandchild and Tom’s youngest, Elizabeth Pendleton Knox. Observing an old family tradition, she carried the newborn girl to the attic- the highest place in the house, so that little Elizabeth “would always be high-minded.”

Loula’s joy over Elizabeth’s birth was short-lived, however. Two months later on New Year’s Eve 1918, son Tom was bicycling home from his Washington job when he passed out on the bridge to Roslyn. Unconscious, he was taken to a Catholic charity hospital in Washington with a diagnosis of Spanish influenza. Apparently he awoke in the ward during the night and tried to close an open window by his bed. He passed out again and expired on the floor beneath the open window, where a nurse found him early on New Year’s Day. Thomas F. Knox was dead at age 30, leaving behind his 27-year old wife Elizabeth and three children under the age of five. His obituary noted that he was a “young man of high Christian character.” After a service at St. George’s he was buried in City Cemetery.

Loula and Lucy both found happiness again. In 1925, while working for the Red Cross at Quantico, Lucy, now age 35, met and fell in love with a young marine lieutenant in the diplomatic corps named Louis Eugene Marie’ Jr. Some time after their wedding at St. George’s, Loula let go of her boarders for good and spent the remainder of her long life traveling the world with her daughter and son-in-law. She died in 1946 and is buried at City Cemetery.

The photos and letters quoted are part of the Douglas Knox collection at the Central Rappahannock Heritage Center in Fredericksburg, VA.