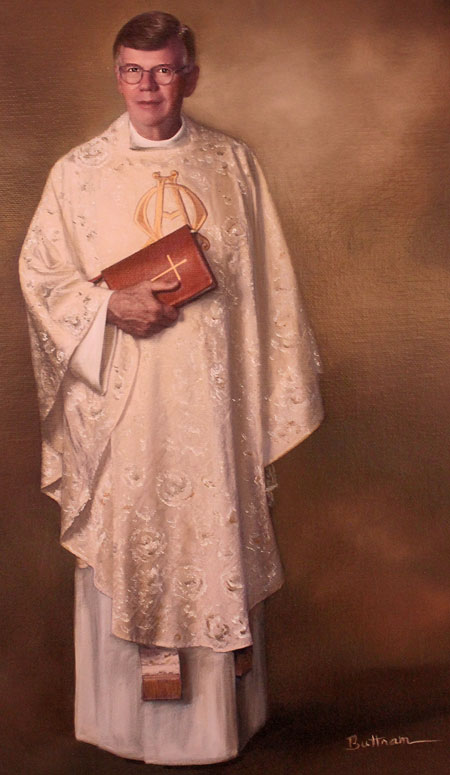

[The interview was done for the 300th anniversary celebration of St. George’s parish. This is an oral history with the Reverend Charles R. Sydnor, Jr., assistant rector, 1973 – 1976 and rector 1976 – 2003, at St. George’s Episcopal Church, Fredericksburg, Virginia.]

Today is, August 14, 2018. I am Beth Daly from Historic Fredericksburg [Foundation, Inc.]. I am with Barbara P. Willis and Judge J.M.H. “Mac” Willis, Jr. We are here at 175 Rogue Lane, Heathsville, Virginia, to interview the Reverend Charles R. Sydnor, Junior. I am going to ask him a few questions and we will get the interview started.

Beth Daly: And your name is?

Reverend Sydnor: Charles Sydnor.

Beth: You’re a junior?

Reverend Sydnor: I’m a junior.

Barbara Willis: And your middle name, we must have that.

Reverend Sydnor: Charles Raymond, named after my father.

Beth: And you were born?

Reverend Sydnor: In Kinsale, in Westmoreland County, February 4, 1944. I’m a native of the Northern Neck.

Mac Willis: What was the month and day you said?

Reverend Sydnor: February 4, 1944

Mac: February 4, 1944.

Beth: And the Sydnor name is very prevalent or prominent in this area?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, the first immigrant and the only one, came to Lancaster County, nearby, in 1666 from Kent in England, and all are descended from the one person.

Beth: You went to school here, locally?

Reverend Sydnor: Washington and Lee High School in Montross, followed by the University of Richmond in Richmond, and then I went to the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria.

Beth: And your father, what did your father do?

Reverend Sydnor: He was the barber at Kinsale. He cut hair until he died in his shop one month before his 91st birthday.

Beth: Good life, good long life. And your parents’ and your family’s religious background was Episcopalian?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, for several generations.

Beth: For several generations. And you have lots of relatives.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, many cousins, but I have just one daughter and three grandsons.

Beth: Yes, I know your grandsons, a little bit. Because I swim at the Y [YMCA], so I see Charlie, Jack and…

Reverend Sydnor: Max.

Beth: And I know Becky [grandmother], and Becky said to tell you hello.

Reverend Sydnor: Oh thank you.

Beth: Did you have siblings?

Reverend Sydnor: No, I’m an only child.

Barbara: Charles, what led you to want to go into the ministry?

Reverend Sydnor: Well I think in the’60s, there were many of us who after the assassinations of Dr. King and President Kennedy became disillusioned with any hope for politics or for the future of justice and I had I think, a kind of vague, ill-defined nudge, about well, maybe I could do something to make a difference in the way life goes for lots of people and I went to see Bishop Gibson [Rt. Reverend Robert Fisher Gibson, Jr, tenth Bishop of Virginia, 1907 – 1990] who decided to take a chance on me, and encouraged me to, to even though I wasn’t well-defined in what I sensed was a call to ministry; he said I want you to see if this is your calling by exploring it with others and over time that vague, fuzzy call became more defined. Yes, I want people to know the love that God has given us through Jesus Christ and I want people to know about the dignity of every human being, and I think that the Gospel will make a difference in the world, does make a difference, and I will do my part proclaiming it as best I can, so it became more defined.

Barbara: How old were you when you entered seminary? Had you worked before?

Reverend Sydnor: No. I made what I would call in retrospect, “the mistake,” of going straight from college to seminary with no work experience. And I sort of corrected the mistake or at least it was a big gift to my life that the seminary offered what they called a church-and-society program where seminary students could work one year, a year in various venues and one was industry. Another was chaplaincy, another was the political arena. And there were some others and this was the invention and brainchild of John Fletcher [Dr. John Caldwell Fletcher, Jr., former Episcopal priest and biomedical ethicist, 1932 – 2014] at Virginia Seminary and I thought, well, okay, maybe this was an opportunity to get some experience in the lives people lead that I had not led. So, I went to work in the inter seminary church-and-society program for one year in the industrial end. I moved to Raleigh, North Carolina, and I worked for one year for IBM. There were four of us in that program. I was at IBM; other students: one was at Peden Steel; it was sort of a sweatshop kind of operation. Somebody else was at GE [General Electric], and the fourth I don’t recall. Anyway, we met with Dr. Donald Schriver [Reverend Donald Woods Schriver, Jr, Presbyterian minister, b. 1927] who went on to become a fairly famous scholar. We met in a weekly seminar to process what we were doing. I wrote a paper called the “The Corporation as a Religious Surrogate.” IBM had, in those days, a discipline that employees had not only to dress a certain way, but they also went through quite a ritual to become sort of indoctrinated in IBM. It was sort of like a baptismal or confirmation class and the company became very much the life of many of its employees, there were picnics on the company grounds; for many people, IBM was their social life. Later, it was interesting to see that many people who retired died much earlier than others in other professions, maybe because they missed home. IBM had become their life and there was not much life at that, so, it was not a good thing necessarily. But it was fascinating. They started me out looking at the 1403 Printer which was in those days as big as this sofa, a massive thing. But it greatly expedited the ability of companies to make copies and do things. So they took me to see the thing working; it was interesting, to see the end product, and to see what benefits it gave to the world. And then they took me back to the assembly line and gave me a job for a couple months doing an annealing process. Basically it was one little piece you had weld to another just as fast as you could, eight hours a day. And for me it was maddening, but for the people around me who had it as a career, some of them really loved it. But later IBM’s design in cooperating with this program was to place me all through the company. So later I wound up in the expediting department where I was trained to expedite deliveries of the necessary raw materials for the manufacture of these printers. And that was kind of fun because they loved to throw money at it. I mean, I was authorized on occasion to charter a plane to bring one part in so the deadline could be met. That was fun. I also worked with people in that department who had bought the stock option and were already millionaires. Interesting. But a very good experience. I think a symbol of what the experience meant to me, was when I came back to seminary for my senior year, I had been living and continued to live in what was called St. George’s Dorm, a three-story building. This was before cell phones, mind you. So there was one phone booth on the first floor in the dormitory for all the students, twenty-some of us in the dormitory. Well that was ridiculous. It never occurred to me that it was ridiculous when I lived there the first two years, but the first thing I did was to order a phone to be installed in my third floor room. It never had occurred to me to do that before. But that’s one of those symbols. Okay, I lived on my own for a year, I now knew had some flexibility. I’ll never forget, Ben Booker, bless his heart, a great guy, came romping over in a rain storm and said to me; you know you can’t put in a phone in the room. I said but I have already done it. He said you know you have to pay for it. I said yes, I already have. He said you’ll have to take it out when you move out. I said, I’ll do that. He said, well okay, I guess. So I had the first phone in any private dormitory room in Virginia Seminary as a result of a year in this program. A further explanation would be to say in that senior year, not necessarily that my grades were any better, in fact, they may have been worse, but relating the scriptures and the study of theology to real life issues came much easier and much more readily. And that was a gift. That was a relief, a good benefit of the program.

Barbara: From there, when you graduated, you didn’t go straight to a church?

Reverend Sydnor: No, but I think this also probably also a fruit of that one-year experience. The Episcopal church had seen its money dry up to some extent because of controversial issues. And Bernie Johnson, the Missioner of the Diocese called me and said, Charles, we have had a church site dedicated and given to us by the builder and developer of Sterling Park in Loudoun County. But, we don’t have any money to pay anybody to start a church. So, I wanted to talk with you about the possibility of your considering going there to start, a congregation, but you would have to be self-supporting. I said, Well, okay. He said I think the developers may be open to this concept. So I went to meet with David Wilson who was the vice president of United States Steel for that location; they were now the developers; having acquired the development from Broyhill, who had started it. And for David, who was an inactive person as far as church was concerned, but, I think, Roman Catholic in background, it was a spiritual moment. He got enchanted by this idea. Back then, a non-stipendiary or worker-priest was not table conversation, nor a household word; few people knew this, it was bizarre, there was no model for it at that moment. So David said, I think this could work. We’re going to build a rec center and you could staff the executive director of the rec center and you’d have flexibility with your time. If somebody was in the hospital and you needed to see them, you could go, you wouldn’t be tied to a regular discipline, which I had talked to him about: if you are going to start a church, you have to have some flexibility with your time. You can’t be locked into an eight-hour job and just go home. He called about a month later and said, “Sorry Charles, that rec center is on hold, it’s not going to get built right now. But, I will sponsor you to go to a real estate class taught by Marilyn Koslow in Alexandria. You can take the real estate exam and if you can get qualified you could come and work for our general brokerage firm, Dulles Sales Company, that we are starting right here.” He said the development is now four or five years old. People who bought with VA [Veterans Administration] loans are getting transferred, and there are hordes of sales, second sales of homes, with people assuming those loans; it’s really mushrooming. So I said okay. So, I’m in seminary, but other people are cramming for the general ordination exam. And I’m downtown in Alexandria I’m taking a course in real estate, wow! Ah, and, how do I say this correctly? It was a comeuppance to this Phi Beta Kappa graduate to fail a real estate exam, which I did the first time. So I had to retake it, but I passed it. They were very strict; you had to dot your Is and cross you Ts. The comma had to be exactly where it was supposed to be. Of course this was writing contracts. They are legal documents. You have to be accurate. Anyhow, once I passed it and I went to work with Dulles Sales in Sterling. And that worked. Starting slowly, our first worship service was with two couples in our living room. Maureen, my wife, and I had just bought that house.

Barbara: At what point did you meet Maureen [Maureen McRorey, 1943 – 2010] in this career and marry?

Reverend Sydnor: I met her, when she was working; she ran the daycare center in Reston. She started it. The developer of Reston wanted to offer all amenities from the beginning for a planned community. So she started the daycare center with three kids, three kids in a big building. A cook, and everything was all available from the start. When I met her, they had 96 kids. She lived above the plaza on Lake Anne; her apartment was above the community center space that the Episcopal Congregation of Reston used for services with Embry Rucker [Reverend Embry Cobb Rucker, 1914 – 1994]. He had been helping with her books at the daycare center since he had a business background. And he asked her in turn to supervise young kids on Sunday morning and I was a seminarian assigned to him, so there I met her.

Barbara: As a seminarian you met her?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, as a seminarian I met her. And she lived directly above the facility so after the service was over I could always go up for coffee.

Barbara: And that led to. . . when were you married?

Reverend Sydnor: I met her in my senior year. Well let me see, we met that fall, and I asked her to marry me the following August, August 4th. And we then wound up getting married in October, in fact on Halloween.

Beth: In what year?

Reverend Sydnor: In 1970. Partly because of the schedules of her family’s travels. Her sister and father traveled in their jobs. Halloween was the date when everyone would be home.

Mac: Can I put in a question? Backing up to your worker-priest experience? I was one of the group that came up to hear you preach one Sunday morning. My recollection is that that service was in a cafeteria of the school. Was it in a cafeteria of the school?

Reverend Sydnor: It was in the community center most of the time; it was in various places. It was also in the school; it was in the school cafeteria for a while. It was probably after when you came, that we got use of the community center and we settled on that. We even used the bank lobby for a while.

Mac: Well you said that the developer provided a location for church there.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes.

Mac: The developer actually built the physical church?

Reverend Sydnor: No. The congregation that I started eventually built a building on that site. The developer had gifted the land to the Diocese. And it is now called St. Matthew’s Church and it’s a growing congregation.

Mac: But that was still in the works when we came up?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes. In fact, one reason I left, was a recognition that we had a corps of people, but I sort of didn’t think I knew what to do about building a church and didn’t necessarily want to get into building a church. In fact, with Embry Rucker I had very much been sold on the concept of the church might be better in its mission without owning a building. And one of things that was interesting in Sterling, was that when the congregation didn’t pay me, and when we had no expenses for a building, and our overhead was mainly buying bread and wine for the Communion. But basically all of the offering that the congregation made, almost one hundred percent of the collection was given away. What do you do with it? It was a constant confrontation with purpose. Why are we here? What should we do with it? What shall this body of Christ do? And we did some pretty interesting things, you know, with a small group with more money than you’d think we’d have.

Mac: So what did you finally decide, how did it work out?

Reverend Sydnor: Well at that point, when I left, I recognized that the next step was going to be getting more organized, having adult education programs on a regular basis. We were growing some, and that the next step was going to be, maybe, thinking about, okay, what kind of a facility will we have on this land, how do we go about that, but I just didn’t feel called to work with that building program. In fact, what I told my wife, and she always reminded me of that, was that I thought maybe it was time to go someplace, a more traditional church for a couple of years and have that experience of leadership and then go back into the mission-starting business. After we were at St. George’s for about twenty-something years, my wife once said to me, this the longest two years I’ve ever experienced.

Mac: What happened is that you got caught. We grabbed ahold of you and we wouldn’t let go of you.

Reverend Sydnor: Well I liked you too. I did like the congregation. During the time I was at St. George’s, downtown basically died and revived. So there was a constant challenge of issues in the community to deal with, and not just the church. That was part of what kept me. There was always something I wanted to finish. Or something I wanted to start anew, in terms of programs.

Barbara: So it was in 1973 that you came as the assistant to Tom Faulkner [Reverend Thomas Green Faulkner, Jr., 1908 – 1996].

Reverend Sydnor: Yes. I began work as I recall, on November 1. We actually moved into our house, which had been occupied by your [Mac’s] grandfather [Benjamin Powell Willis, 1866 – 1946], called the Steamboat House, [Barbara, the Steamboat House 1116 Prince Edward] on December 20, with the roof leaking. In fact, one anecdote that you have to use, is when we arrived, the Masseys’ moving van had not left. So our moving van had to sit and wait a little K until they finished up. There’d been much snow, and it now was raining on top of the snow. I had earlier tried to have the roof repaired, but obviously it didn’t get fixed, so we had a couple of buckets in places where the roof was leaking. The house was sorely in need of restoration, as you may know, with wallpaper falling and all kinds of things. So, about midnight when we finally got going on moving in there, one of the movers looked at me and said, are you a preacher? I said yes. He said, I don’t think a preacher has no business living in a place like this.

Barbara: And you all did a wonder job.

Reverend Sydnor: We finally got it restored, and we did most of it by ourselves.

Barbara: And what where you, about 29 years old?

Reverend Sydnor: Twenty-nine years old.

Barbara: Had you interviewed with Tom Faulkner before you decided whether or not you were coming?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes. And as you said a committee came to hear me. I can’t remember all the other members but Clyde Matthews was one of them.

Mac: Clyde Matthews. And at that time, Barbara and I lived up behind the College. Clyde and Mary Lou then later bought that house.

Reverend Sydnor: That’s right, they bought the house you lived in and they’re still there. I’d forgotten that.

Barbara: So at the end of three years, your two-year idea sort of melted?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, it was a strange move, in that my income went about in half and my expenses doubled.

Barbara: So the search committee, which I think Mac was on, you passed the search committee. You were there and lasted close to 30 years.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, I was there as the assistant two and half years when Tom [Faulkner] retired and then 27 years as Rector more or less.

Barbara: And that was some sort of a pattern of St. George’s preachers staying long.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, it’s a very interesting phenomenon, Walter Wink [the Reverend Dr. Walter Wink, 1935 – 2012, Methodist minister, biblical scholar], who is now deceased, wrote a book about the demons and angels of churches and he wasn’t writing literally about demons and angels, he was writing symbolically. But he said, and it’s interesting, he had some research to document this, that congregations tend to have a pattern that continues long after the precipitating event is mostly forgotten. It may have started for all kinds of reasons, but it tends to perpetuate if it’s going okay. Some congregations have clergy for a very short time, and sort of chew them up and spit them out. Other congregations have clergy for a very long tenure and like that, and expect it, and St. George’s, obviously, is that kind of place. With Ed McGuire [Reverend Edward C. McGuire, 1793 – 1858] there for 45 years [1813 – 1858] and Tom Faulkner [Reverend Thomas Green Faulkner, Jr., 1908 – 1996] for 30 years [1946 – 1976] and now my being there for a total of 30 years.

Barbara: Let’s talk some about your agenda as a minister in Fredericksburg at this time what you saw was the greater, greatest, and great need in the community as well as for the church because you have used, I think, the term social justice to express your goal of what you felt should be done.

Reverend Sydnor: Well, I think that one gift to me and to the Episcopal church at large was the new prayer book, which, although it was a struggle to accept for many people for a while, contained the baptismal covenant and the way it’s worded through which we four times a year at least, used to renew our baptismal covenant, and that language becomes part of our identity and part of our mission became respecting the dignity of very human being. So one of the first things I did with Anne Nere’s great help, was start hospice, which to me is all about respecting the dignity of every human being till their last breath, and enabling them to live as abundantly as they can until that day. I had a great legacy from Tom Faulkner: when I came the Big Brothers and Big Sisters program used the space upstairs at St. George’s building as their office space and Tom Faulkner had gotten them, I understand, to come to Fredericksburg to start the program. Of course Tom and Mary Faulkner were highly involved in having foster children and all of that dimension. Tom had been a champion of social justice on the equality for all races and paid high prices at times for his convictions. So, there was that legacy of St. George’s looking towards justice and respecting the dignity of the people and developing programs that didn’t exist where they needed to exist. I, sort of, that legacy and built upon it.

Barbara: Well, what were some of the other programs?

Reverend Sydnor: Well yes, of course, hospice was the first. During the time that you were considering me to be rector at St. George’s, I found that it was an uncomfortable time in that I had said yes to being considered, and then I was being evaluated and it felt like, well, maybe I shouldn’t, if I’m to be here temporarily make any major changes that somebody else may have to follow up with. Or maybe if I don’t do that people will think I’m not qualified for the job, and think he doesn’t know what he’s doing. So it was uncomfortable either way I went. And during that time, I went to see Loren Mead [Loren Benjamin Mead, 1930 – 2018], who was then head of the Alban Institute in Washington. I said, you’ve studied all this phenomenon of parishes changing leadership after long-term ministry, what may I expect? And he said, well, you know, I think it will take you at least a couple of years before you finish cleaning house, tidying up things, working through the grief of the long-term pastor leaving, and people adjusting and then you will see, maybe, you will see the first time you start something, a totally new venture you totally want to own.

It was about two years before I began to work with the concept of hospice. And that was very interesting. Anne Nere, bless her heart, had called me; she had heard me talk about hospice and called me about a six o’clock in the evening, about a meeting at the Community Center at 7 p.m. It was about the possibility of what hospice is like, what the needs are for this area. She asked if I could go with her at seven o’clock? Okay, so we went and learned about the need. And she was very excited about it, I was also, and we began to think out loud how this might happen. As you may or may not remember we had a program called “Venture in Mission of the Diocese.” Tom Rohr, whose widow Brandon lives nearby in the community here, was head of that. Anyhow, maybe you were you on the Vestry, Mac? I don’t remember that at that point. You may have been.

Mac: I don’t recall.

Reverend Sydnor: Although I’d have to check the dates, I can’t remember them exactly, but this is about the time that we were looking at our own needs to renovate the building, to do some restoration and when I presented this proposal to our Vestry, that the Diocese was asking us to be part of this nationwide $100 million “Venture in Mission Capital Campaign for the Episcopal Church.” A number of people said, well you know Charles, we can’t do that right now. We’ve got all kinds of things going on. We don’t want to take away from our budget, nor to take away from our capital campaign, nor do we want take away from our own renovations here, and I think I said something like, give it chance and if nothing happens, nothing happens. There were $22,000 in pledges from St. George’s to that program and I went to Richmond for meeting about the “Venture in Mission Campaign in the Diocese.” And Tom Rohr, who was chairman of the committee, came to me and said, Charles, have you thought about the good you could do in Fredericksburg with some of this money. I said, well Tom, a few of us, have been talking about hospice, but nothing is real yet, we’ve just been talking about the concept, and what we might do. He said, write something up for me, I’m going into this meeting. So, I scratched out a few notes on a scrap of paper. I gave it to him and he came out of the meeting and said well you have $11,000 for a start, and that was half of what we gave. Interestingly, we came back and with that seed money and began to develop the concept. Anne Nere really had all the organizational skills to pull it off. So, I went on the campaign trail as it were. I think I spoke to every civic organization in Fredericksburg, the Kiwanis Club, the Rotary Club, whoever it was that had a breakfast, lunch, or dinner meeting. I talked about hospice and the need for it, because nobody knew what it was at that point. And finally it began as a free-standing operation. It’s still there.

Barbara: I think that was in the year 1981.

Reverend Sydnor: Sound’s right to me, 1981.

Barbara: And then you went to work on several other very other important events in the community’s life, Hope House [Loisann’s Hope House]. You had an experience with a homeless person.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes we did. In fact, I used that in a sermon recently and that’s an aside I won’t go down, or maybe I should. The Virginia Episcopalian (TVE), in writing up what happened with our developing Hope House as a home for the homeless, described this man we met early one morning at Faulkner Hall who was homeless and told us what was happening on the street. His name was Roger, and called him our drunken angel, and he was, if not drunk that morning, he was sure close to it, he was getting over it, but he was a messenger about the plight of the homeless. I used that story recently at historic Christ Church. After the passing of the peace, a very nicely dressed African American gentleman with vest and tie came in with trumpet in his hand and said, “I want to blow my trumpet three times and tell you what’s wrong with our country.” And I said, “Well, okay, briefly you can speak.” I figured that might be less disruptive than saying, no, get out. I didn’t know what I was facing. So he did say a few words about a house divided against itself cannot stand. And the country is divided and this is a problem and we of faith must try to heal it. He wanted to blow his trumpet three times and he did and finally, he left. Well after the service several people said, was he another angel? Anyhow, back to the beginning of Hope House; the Brotherhood of St. Andrew, six of us, met in Faulkner Hall. We met this fellow, who was a Vietnam vet; he told us a story of homelessness and we began to think about it. Somebody said homelessness, somebody should do something about this. I said well, we’re somebody. We literally took our coffee can money. (I called that, in the sermon I preached not long ago, our loaves and fishes, it was what we had to offer), and we bought an ad in the Free Lance-Star; this was before Face Book and all our current social media, so if you wanted to tell somebody, you had to use the paper. We invited anybody who was interested in the problem of homelessness in Fredericksburg to come to St. George’s for an evening meeting, and about 60 persons came. Out of that came people willing to volunteer to form a board of directors to start to look at this. I think we had three dimensions: The scope of the problem was one; What other people in other areas were doing about this, and then finally, to conclude, what should we do? That took about a year to do that homework. And were you [Mac] on the Vestry when we bought the Lafayette Boulevard [property]? I don’t think so?

Mac: I don’t remember.

Barbara: [Mac] you were on the Vestry earlier, ’65 to ’75, so this was later.

Mac: I stopped being on the Vestry when I became a judge. I decided it was inconsistent positions.

Reverend Sydnor: In any event, Fritz Leedy, who is still living and doing fairly well at age 95, was very enthusiastic about this and he had good leadership skills. He was the Chair of our board and took it through the next steps. It was Fritz who found the house on Lafayette Boulevard. And he said this is a good property for us. It was rundown and needed help. And of course, everyone was in favor of doing something for the homeless, but unless it’s in your backyard, and then, nobody seems in favor of it. But we went door to door, to all the neighbors around that property saying we want to be a good neighbor. It is a myth that property values go down and crime increases in a neighborhood where there is a home for homeless people, we can prove it to you that it hasn’t happened. It’s not the case. Anyhow, I really was proud of our Vestry the night we presented to the Vestry the concept of doing this, not two hots and a cot, but a home for families until they can get back on their feet, offering guidance and counseling and support, and a kitchen for cooking with donated foods and saving their money for housing later. And the Vestry, on the advice of Fritz, who had seen the property along with me; I’m pretty certain that nobody on the Vestry had seen that house, but we presented the concept, presented the idea and the Vestry bought the concept and the property, sight unseen, for $86,000. And I came home from the Vestry meeting and my wife said, how did the meeting go? And as I said in my recent sermon: it was a miracle, they bought the place sight unseen. I mean, conservative, responsible business people don’t do this. I think the spirit was at work, it really was.

Barbara: Yes, did some of that money come from the recent sale of the old rectory on Cornell Street.

Reverend Sydnor: It came from the sale of the rectory. And some people had other designs on that money. One was to invest in an endowment. Of course we eventually got it all back. Because it seemed beneficial to the obtaining of grants for this kind endeavor that eventually the church not own the building. Fritz Leedy, bless his heart, then got the Board of Realtors to put up a house for a raffle. And all the money went to Hope House and enabled the Board to purchase the house from St. Georges; we agreed to sell it for the same price at which we bought it, although we had invested much in it.

Barbara: And it’s still going strong.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, and it’s still going strong.

Barbara: That was 1987 and it’s now a very essential part of the community.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, Charles Taylor Lewis was on our board worked with us for a long time. He was a member of the Brotherhood of St. Andrew. He and Betty Faye live near here and I recently had his funeral. I talked about his faithfulness to the Gospel at his homily for his funeral and the example was of Hope House. We worked together on it.

Barbara: Well that was certainly then another step in your feeling of how to express social responsibility. Tell us about FACRO [Fredericksburg Area Community Relations Organization]

Reverend Sydnor: Fredericksburg Area Community Relations Organization sounds so innocent. This was not my brainchild. It was conceived by George Van Zant, The Rev. Lawrence Davies [then Mayor of Fredericksburg] and Johnny Johnson and I don’t remember who else, but they were some of the principals. They wanted to have some effort to continue to work for social justice in Fredericksburg. One issue we faced was that there were no minorities in management in the financial institutions of our area. So one of things I recall that we did, this quiet, little, innocent group, was write to the Free Lance-Star. First we wrote to banks, saying we are concerned that we don’t see any minorities in management and we’d appreciate a response from you saying why this has not happened and what you hope you could do about it. We’d be glad to publish the results of these letters and your responses in an article in the Free Lance-Star. That did not make some people happy. But it did result in a number of things. One was a discovery that there was a pool of African Americans and other races qualified for jobs in bank management who had an organization. You could go to that organization and you could get applicants. If you wanted to pursue it, you could. And so, it wasn’t too long after that, that one bank, did have the first person, a non-Caucasian in management in a bank. Several indicated that they didn’t know how to do this and we gave them some insights from what we had learned. We did also talk about the lack of minorities in the teaching profession. And when we were told there were no minority applicants we said to the superintendent of schools, what are you going to do about it? What have you done about it? Why don’t you go to the state teachers’ college? There are plenty of people qualified to come teach in schools here. And if they haven’t come to you, you can go to them. There was a response to that, a positive response. There was an increase in the number of minorities in the teaching profession. We did talk about the unfairness of the testing system. And this is where I don’t have all the right jargon, but clearly when you began school, there were tests given, to determine, shall I say aptitude, I don’t know what language they used then. But the tests, it seemed to us, had a decidedly upper middle class, white bias. For example, one thing that stood out in my mind was, they assumed that families would have Newsweek or US News and World Report or magazines like that available and on the table because some of the questions on the test implied knowledge that was in things like which people struggling for money, white or black, wouldn’t have. So what happened was kids got tested and in our opinion, dumped in the slow group when they really weren’t slow, they just didn’t have the resources at their disposal, that the tests assumed you had to have to be counted in the fast learners. So some of that began to change. I can’t give you all the details because I don’t know all the details. But we did have some impact in seeing some of that change. And that was sort of quietly behind the scenes.

Barbara: Then you became aware of a need of a different kind of homeless. Ones that didn’t qualify for Hope House.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, the mix of a homeless family living in the same facility as a single man or woman who is homeless, off the street, maybe with addiction problems, or maybe not, was not a good mix. Families said it didn’t work. We also saw that there were some homeless people, who because of maybe mental illness or personality disorders, or whatever, weren’t going to do anything but live on the street. They were too wounded or too diseased to see any other choice. Yet, we didn’t want to see them freeze to death in the winter. So there had to be a safe place for these folks, we thought, to at least have food and shelter when it was life-threatening cold. That’s where the idea evolved of having a facility that is basically known in the trade as “two hots and a cot,” a one-night operation. That’s evolved into the Thurman Brisbane Homeless Shelter.

Barbara: She [Thurman Brisbane] was a member of St. George’s, very interested.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, she was a member of St. George’s, and wonderful, dedicated soul. I think I read online about her recently, which triggered my memory. Thurman was famous for saying something like, “if I have two coats and I know someone who has none, there’s something wrong and I must fix it. It’s that simple.” She also was a very sophisticated, intellectual person who was head of the school at St. Paul’s Church at Alexandria. So she might express herself simply, but she was profoundly thoughtful, theologically astute, and well-read.

Barbara: That was in the early 1990s I think, when that started. But before we leave the ‘80s period, there was something else that was going on that you were somewhat avant-garde and that was the acceptance of gays in the church.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, yes. A number of things had happened. One, my personal convictions, over the years, as a result of reading and in counseling experiences with people, had begun to change. And I had begun to recognize the truth, which I think is the truth, that people are born with their sexual orientation. How they act it out can be moral or immoral, illegal or whatever or for good, but they are born with it basically, and I think there is ample evidence for that. Well what do you say about that if you are born with it? If we are heterosexual, we say it’s God-given. It’s who God made me to be. If you are gay, can you say that? What do the scriptures say about it? Not much, scripture doesn’t say much about sexuality as we understand it today. Because scripture talks about sexuality from the point of view of a number of things. One, you, the sin of masturbation is that you shouldn’t waste your seed, if you are going to live into your old age, you’d better have a lot of kids to take care of you; nursing homes did not exist then in that culture, in that time. So the problem, the sin of Onan in Genesis, we would understand, perhaps, someone might say, he masturbated, but in those days, the problem was he wasted his seed, it did not go to create life to sustain him in his old age. You had a responsibility to be sure to have enough progeny around to take care of you. That was one thing.

Barbara: You wrote; didn’t you write something?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes I did. I wrote a piece about the 11 scriptural passages, if I’m remembering right, that have to do with homosexuality in some way or other. And I wrote a detailed explanation of those from the point of view, from my point of view, from the point of view that I thought was faithful scholarship. I mean, the word homosexual did not even exist until the eighteenth century.

Mac: Not exist till when?

Reverend Sydnor: The eighteen century or maybe later, in a way we use the word now that just didn’t exist. The Bible didn’t deal with sexuality as we think of it. The Bible didn’t know about faithful committed relationships, at all.

Mac: You are talking about the term, not the concept.

Reverend Sydnor: The term.

Mac: They had other terms that were less polite.

Reverend Sydnor: But anyhow, I went through a personal conversion with this. Part of this was having a young man in counseling early on at St. George’s who came to me, who was referred to me, and he had been in partnership for 11 years and he and his partner had become what I would not have then called, but soon would, divorced. Because I wouldn’t have called them married then, but soon did. But in seeing him, I realized he was going through exactly the same pain as that anyone who had loved another person would go through when that trust has been broken. And he was in pain. Actually with no background, in doing pastoral care for a gay person going through a divorce, everything I knew about helping people through a divorce, I could apply to helping him. I began to read more about this stuff and I came out with the conclusion that you are born this way, people have a right to love, they have a right to relationships. The Church should recognize this right, and it does.

Barbara: Didn’t you begin having an evening service, a Eucharistic service for gay people who felt uncomfortable?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, in those days, there were plenty of churches where gay persons did not feel welcome, either overtly, often overtly they were not welcome, it was very clear, or covertly, they got “the look: Why are you here? So, the Integrity organization of the Episcopal church which, was designed to support gay rights, had a service at St. Clements in Alexandria. So, they came to me, I guess, having heard the reputation I had of being a gay-friendly pastor, and said, would you be willing to host a service since some people come to our services at St. Clements from Charlottesville. And it’s too far for them. Would you be interested in having a service at St. George’s, which is more central? I said okay, so we did on Friday nights we did have an Integrity service, and it certainly was an avenue to some people returning to the faith. Without mentioning names, and I can’t remember them anyhow, for example, definitely one lesbian couple came to back to church through that service and later became members of St. George’s and one became a member of the Vestry. So, it was an entry point to come back.

Barbara: Isn’t that when the bulletin started to saying the welcome, and included, regardless of sexual orientation?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, I presented it to our Vestry. But let me tell you why that came about. I went to the convention of the Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. What year was that? I don’t know. I wasn’t there as a delegate; I was there doing a job as a member of the Ecumenical Commission of the Diocese to work with certain issues with full communion with the Lutheran church. But at that convention, Westboro Baptist Church was there, as they often did then, adhering to the law rigidly, the right number of legal feet away from us on the street, with placards saying Fags go Home, God Hates Gays, and yelling and screaming on the street. It was a terrible scene; it was very painful. I got there early and went to a Sunday service at a local Episcopal church, because it was walking distance from the convention center where I was, and the convention had not started. I went to a little tiny Episcopal church, that had an endowed music program, a trained chorus. Behind me in the pew there were two guys with sort of green hair, dressed, very casually. At the peace I turned to exchange the peace. And they did not go up to Communion. And afterwards, when I spoke to them, after church, I said, you didn’t go to Communion. The Episcopal church welcomes all baptized persons to its Communion. They said oh, well, we’re gay, we can’t go. And I said, well, in the Episcopal church, that wouldn’t be a barrier. He said, really? I said yes. He said, could we talk about this? I said, okay. I said, do you want to do lunch? He said, well, there’s a restaurant nearby, but it’s a gay restaurant. I remember I saying to him, but do they serve food? He laughed and said, yes. And I said, well, I’ll go. So we had a wonderful conversation about their horrible experience with a fundamentalist church that had kicked them out because they were gay. And I took them to the Integrity booth at the convention. They got to meet a gay Episcopal priest. They couldn’t believe it, they were enthralled. They were excited that there was a place in the body of Christ for them, in a church like ours. So that’s when I came back to the Vestry and said, I’ve thought about this, I’ve prayed about this; I really think it’s not enough for us to say all are welcome. I think we must be overt about it; we must be clear about it; we must be particular about it. And that’s when I drafted the statement which is like this one used now, but I like what you have now better than what I wrote. But it’s the same sense. I presented it to the Vestry and said, okay, we need to talk about this, we need be honest about our feelings, we need to talk through it. I said not everybody is going to like this, perhaps, and lets just talk about it. We talked about it from the point of view of the baptismal covenant, and in the end, if I remember correctly, in the end, we were unanimous in affirming this and it started appearing in the bulletin. And that was fascinating, because people would come to the front door after church and shake my hand and say, thank you for the welcoming me and wink at me. Interesting.

Barbara: And now, it’s even, you might say now, in today’s terms, more inclusive, since you are welcome at St. George’s Church regardless of race, nationality, sexual orientation, gender expression, or tradition.

Reverend Sydnor: And I think, had I stayed, I would have certainly wanted to have endorsed that as well. It seems to me it is certainly part of respecting the dignity of every human being and loving your neighbor as you love yourself. It certainly is part of that little verse from Titus, saying God shows no partiality, but in every generation…

Barbara: An interesting experience that St. George’s Church had when you were there, in response to feelings about gay people was when the Westboro Church from Kansas decided to come to Fredericksburg.

Reverend Sydnor: I was proud of St. George’s response. Yes.

Barbara: Mary Washington College was putting on a play [The Laramie Project about Matthew Shepard’s murder], based on the Laramie, Wyoming, incident and you can tell what happened.

Reverend Sydnor: We had a consultation with the police chief. They were coming. We understood they would be across the street, they were keeping their legal distance from us and would be delighted if we responded in any kind of way that gave them occasion to sue us, and were ready, willing and able to do it. The best thing we could do was respectfully ignore them and show them by our attendance that we were not intimidated by them. I think I wrote a letter to the congregation saying this group was coming, we didn’t necessarily expect violence from them, but we did not wish to engage with their hatred, in anyway, but to ignore them; we were there to worship God. So I hoped the congregation would show forth a good attendance. Well the eight o’clock service that Sunday had, as I recall, more people than Easter. It was wonderful. Everybody came, walked in, they were quiet, they were respectful. Westboro could do nothing but stand there and look like idiots.

Barbara: The had their signs, and one of them was, “Episcopalians are sinners.” I said to somebody afterwards, aren’t we all sinners?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, aren’t we all sinners? Another thing that had happened that was part of the story, I told the Vestry, it was part of promoting the statement on the bulletin. We had hosted a worlds AIDS march at St. George’s, the first. There was an assembly at church right after the marchers came back, there was a reception downstairs. I made some comment at the assembly, I wanted to welcome all people there and certainly would like to welcome all people present to our services on Sunday morning. And at the reception downstairs, one person came to me and said, no one has ever invited me, a gay person, to church before. So I told that to the Vestry. Maybe that’s another reason we should be overt about this. I do think there is anecdotal evidence currently, that churches that are the most inclusive are the most growing of the churches in the Episcopal church.

Barbara: I think in all churches.

Reverend Sydnor: I think in all churches. I don’t have data, statistical or analytical data, I just have anecdotal data, I see it happening. St. Stephen’s, Heathsville, for example, has a number of gay couples and they will even have a sign out front that says, “We welcome the marriage of Jim and James” or whoever it is; they are very overt about it and they have grown.

Barbara: Well one of the other things that you initiated for St. George’s or St. George’s and you, was the Moss Free Clinic.

Reverend Sydnor: Oh yes.

Barbara: That was certainly something that is still beneficial.

Reverend Sydnor: Jeppy [Dr. Lloyd Fick Moss, 1915 – 2006] was a wonderful example of a caring, compassionate doctor

Barbara: This is Jeppy Moss, Dr. Moss

Reverend Sydnor: Jeppy Moss, oh boy. Most people don’t know a lot about what he did. Some people do. I know when somebody died, the son was distraught, Jeppy spent most of the night after the death of the lady with the son, because he cared about him. Jeppy was a remarkable guy, so it’s very appropriate that we would name it after him. I got invited to be part of that. We had a board, I can’t think any of the doctors on the board. Isn’t that terrible? There were a number of people from the hospital engaged. We had a dialogue about how to do this. What it would be like and got it going. A member of St. George’s, Janice Hales, was the staff person for that for a good while. And it worked. A lot of people donating their time. One of the things that intrigued me was that, although we didn’t model it quite after their experience, but the Church of Our Savior in Washington, DC, had started a free clinic because they expected every one of their members annually, to make a pledge of ten percent of their time, to do something for somebody. And it had to be written out. And it was celebrated by the congregation. So the idea of starting a free clinic came about there with nurses and doctors and other people who were needed, tithing ten percent of their time, to work in a free clinic. And, it happened. Fascinating, it just happened, because they did that. We didn’t call it all that here, but the same thing happened. People gave of their time, and it worked. It made a difference; it reduced the load on the emergency room. I don’t know where all that stands today, in terms of people using the emergency room as their primary doctor. I guess it still happens, but I don’t know.

Barbara: It happens; it’s an ongoing problem. The Moss Free Clinic. They have a brand new building up next to the hospital.

Reverend Sydnor: Which I’m sure does take some load off of the emergency room, which is a good thing. Something else that might not be on your list, and I can’t remember the timetable, but we started the program through the Salvation Army. We called it the “Community Assessment Program” (CAP). What precipitated that was, St. George’s as well as most churches being on the I-95 corridor got a stream of people coming to the office begging for help. And again, often it seemed they came when we had our own crisis going. And we really didn’t have time for them and but I also didn’t want to dismiss them summarily and seem to discount their dignity as a human being. So how do you handle this? Plus, many people locally, they’d go from church to church to get a few dollars here and there for help. If their rent was due and they couldn’t pay it, and it was $125, and St. George’s could give them $10 maybe or $25, or what we had available, somebody else would give them $25, so they had use their time and a tank of gas going to five places to get their rent money. I thought this was nonsense; this was not the way to do it. Charlottesville had developed a program, they didn’t call it the community assessment program, but through the Salvation Army who managed it, a program of intake, where most churches cooperated, saying, okay, we will have one intake place. Anybody coming for help goes there first. They fill out the papers, they get the data, we will give to that intake group all of the resources, not the resources themselves, but data about the resources we had. St. George’s had all these trust funds available in certain months of the year, we will give that data to this group, so they will know who can help and we will agree to trust this intake process. If this intake process says that Mrs. So and So, who is on my doorstep, really does need $100 for her rent and we have we $100, we will say, God Bless you and give it to you right then, and she won’t have to go to five places to get it. So that’s what we developed. It’s based on honor. I don’t know if it’s still operating, but for a while it was a great benefit, because people didn’t have to go to five different places to find gas money and I think people who needed help, got help. And people who didn’t need help, or sought it to feed a bad habit got led to or at least invited to appropriate resources.

Barbara: Would this be a good time to take a break right now.

Reverend Sydnor: Oh goodness, I guess my squash casserole is too well cooked. I forgot about it.

Lunch break. Interview resumed after lunch.

Barbara: Well, Charles, we touched on many things, that you introduced, not just to St. George’s but actually to the Fredericksburg community, as far as the idea of social churches involved in social outreach. Is there something we haven’t talked about in that field that you’d like to bring up?

Reverend Sydnor.: Well, probably not. I have thought since my retirement about directions I would have gone had I stayed. As I had served on the Stewardship of Creation Committee of the Diocese for a while and I do have a great passion about the mandate to care for Creation and I see that the impact of climate change has devastating impact not just on the planet, but especially poor people, so I think endeavors in that direction are an appropriate call to seek justice for all people. I don’t know what it looked like back then and I’m not sure what it looks like right now, but that’s a place I would have gone, had I stayed.

Barbara: When you retired, it’s obvious you got involved in a lot different of things. Didn’t you work for the Diocese for a while on a part-time basis?

Reverend Sydnor: Well yes, there are several commissions of the Diocese on which I served, and I was chair of the “Ecumenical and Interfaith Commission” for about 15 years, which meant I was the Bishop’s representative at any ecumenical or interfaith gathering and I was an advocate of full communion with the Lutheran church and I spoke at the “Assembly of the Lutheran Church in Virginia,” “The Virginia Synod,” in advocating our full communion relationship and a number of other places and was involved in various dialogues about that. I also went to the “National Workshop of Christian Unity” which occurs once a year in different locations all over the country and our “Episcopalian Ecumenical Diocesan Offices” had their meeting simultaneous with that national workshop. And so I went to all those events. And when I retired, it was interesting, I called, or wrote our Bishop, Peter Lee, saying I find it necessary to retire from St. George’s because of my wife’s illness and the necessity of caring for her and the expense I can’t maintain for hiring everybody for 24/7 care. And I said I would also retire as Ecumenical Officer of the Diocese, and Peter said, No, I don’t want you to do that; think about it Charles, full-time care-giving is quite demanding. I want you to have the opportunity to get away from home overnight now and again. So every time you go someplace at my request representing me, I will pay for the caregivers to stay with your wife. He had some sort of trust fund. So that’s what happened and his wisdom was very helpful. Because yes, those times away were a necessary part of refreshment to be able to keep on doing what I was doing because it was demanding.

Barbara: I don’t know if you are aware, you mentioned our association, that’s probably not the right word, with the Lutheran church, that we now, St. George’s and Trinity, have hired a young adult missioner [Reverend David P. Casey, O.P.] and it’s also being shared with the Lutheran church [Christ Lutheran Church Fredericksburg].

Reverend Sydnor: Oh, I’m delighted. I didn’t know about that.

Barbara: And he’s going to come, I think, he’s hasn’t come yet, and we are going to have an introduction coming soon and this young man that’s going to work with all three churches.

Reverend Sydnor: We still have the covenant we made with Christ Lutheran and that’s ongoing that came out of the time of living into this full Communion.

Barbara: One other thing that’s very much in the news now is the Pope [Francis] announcing very strongly that all Christians should be against the death penalty and that was something else that you brought up, didn’t you, as a minister?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, I have consistently been an advocate of opposing the death penalty as ineffective and in places where it is used extensively, I think that the data exists that it still doesn’t make any difference. I think the data is the death penalty, even where used, doesn’t change the data, the statistics

Mac: One data that it changes, that guy won’t do it again.

Reverend Sydnor: That guy won’t do it again. But the other issue for me is part of that was, I was as Ecumenical Representative of the Bishop, at one point I was a member of the of the Virginia Council of Churches. And the Virginia Council of Churches, part of its ministry, ecumenically, was to stand against the death penalty and represent that stance to the Virginia General Assembly. So we were all part of that process at one point. I think the death penalty denies the second chance to anyone.

Mac: Denies what?

Reverend Sydnor: Denies a second chance to anyone. And at least, if nothing else, on the basis of some past decisions, that were made by error, especially with racial overtones in the background, I thought we had plenty of reason to reconsider what we were doing.

Mac: I think the strongest argument against the death penalty. Let me say first, in all my years as a judge, I feel that I was blessed in that I never was called upon to impose a death sentence. I never imposed one, and I feel blessed at that, but I think the strongest argument against the death penalty is that it’s irreversible.

Reverend Sydnor: Exactly, there’s no second chance.

Mac: You can in effect take away much a person’s life by locking him up. You say the death penalty denies a second chance.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes.

Mac: A second chance at what? It doesn’t deny a second chance to murder your wife, or somebody you’ve come to hate. ‘Cause you’re locked up in jail, you don’t have the occasion to be tempted to do that. But, it’s irreversible.

Reverend Sydnor: What I mean by second chance, there is chance for reform, for repentance, rehabilitation and in some cases, a second chance at life if the error was made and the person was wrongly sentenced.

Mac: Plus, I think that, the implications that follow for mercy are worthwhile.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes. Yes, well said. I agree, I agree.

Barbara: We talked a lot about the church and its outreach, while you were there over your course of twenty some, nearly thirty years, there were changes within the church.

Reverend Sydnor: Oh yes.

Barbara: Starting with the new prayer book [The Book of Common Prayer, 1979] and you came right in, as far as that then.

Reverend Sydnor: Want to see my scar tissue?

Barbara: And with that the change of arrangement in the chancel. Do you want to talk a little bit about that? How it occurred in St. George’s, because when you left, the new Aim 2000 [renovation of the entire St. George’s facility, except the nave, and the replacement of much of the heating, air conditioning, plumbing electrical and lighting infrastructure] was a total change with the choir being moved.

Reverend Sydnor: Well, yes, yes. In terms of prayer book change, I always thought that the way we went about that in the Episcopal church led to false expectations. Namely, we did trial use. Remember the green book?

Barbara: Oh yes.

Reverend Sydnor: Well, the green book, when we used it you were supposed to respond to it and send in evaluations of it, blah, blah, blah. Okay, that’s fine. Except it left the expectation that perhaps, if enough people wanted to change what Hippolytus said in the fourth century, we would. Sorry we don’t do liturgy that way. The way that history and theology needs to have an equal footing. I mean, we can say we don’t like it, that’s for sure, but the implication, I thought, was that if you say we don’t like it, we’re not going to do it. I mean, that was an unfair implication to put upon people. Because, in fact, there were services in the old prayer book of 1928, of the churching of woman after childbirth which were not used because no longer did we believe that a woman was defiled by childbirth. There were some changes that needed to be made, regardless of whether you liked it, just because it was practical. I mean, and some changes were based on the recovery of knowledge of the first centuries of how worship was conducted and what was in the liturgies and how the scripture was read and all these things. I regretted that I inherited at St. George’s, which I guess Tom Faulkner had done that, some sort of survey, you all must have been part of that, of what you thought of the limited use with the green book at St. George’s right? And what I remember about that is a very small number of people had responded to that survey, but the majority were very opposed to any liturgical change. But then, the church as a whole said, okay, we’re going to have a new prayer book. And I heard from people saying, why are they shoveling it down my throat? Well, because we set up some false expectations; if you didn’t like it, we weren’t going to do it. No, that’s not the way it was designed to work. Anyhow, it was a hard time, because we were basically raised on one spiritual diet, as I was too, of morning prayer three times a month, and Communion once a month. We were raised and nourished and sustained with one spiritual diet and now that diet was taken away from us. We were going to have another diet to try. Well, maybe we didn’t want it. So it came hard for many people to accept those changes; I found that sometimes even it was such an emotional issue with some people, that even though there were valid reasons you would talk with the person who could not hear them. I remember someone, I won’t use the name, but I remember who it was, he’s now deceased, saying “show me one thing that is good about the new prayer book and I’ll like it.” So I pulled out a letter from a couple who were ecstatic over the new wedding ceremony, the new wedding liturgy and how much it had meant to them to have scripture and have a little homily in their wedding service and they thought it was just wonderful. And he said, “tell one thing about the new prayer book that is good and I’ll like it.” He couldn’t hear it at all. We were all emotional about it. We didn’t listen very well. So I made some mistakes about all of that and maybe this ought not to be on tape, but I thought at one point, if you are going to make changes, you may as well catch all the hell at once. I really did think that at one point. So I thought if you are going to start using the new prayer book we might as well move to having Eucharist every Sunday which the new prayer book, in its preface says, shall be the principal service of worship on the Lord’s Day shall be the Eucharist; we may as well just do that; let’s get going. Well, of course, there were many negative reactions to that much change from all sorts of people. I understood them, and then there was a Vestry meeting, I can’t tell you when exactly but, I do remember the motion on the matter came up at ten o’clock at night. objecting to our use of Communion and wanting us to return to morning prayer, I forget, how often, maybe it was twice a month or something, and we did, for a while. So, it was a long journey to work through all of that and to begin to discover what it meant to be a Eucharistically-centered community, and what benefits that had for us, and how that was for most of Christendom was central to the life of the church. Our Virginia tradition of morning prayer was an aberration around the Colonial era, partly in repose to the absence of ordained clergy to celebrate Communion all the time, so we got along the best we could with lay-led services in those Colonial days. It was a long hard struggle for many people to accept changes of the new book.

Barbara: Well one of things that it led to was actual physical change in our chancel because of the choir being there and the new liturgy was that the minister would face the congregation.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, let’s turn to that. Words are always inadequate to what things mean, but when the celebrant is facing the altar, with his, his or her, back to the congregation, the symbolism of that is the priest is representing the people to God. And God is somewhere, out there, up there. When facing the congregation, the symbolism is intended to be that the words of Jesus as when he said we when two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them. So the symbolism is Christ, God is present to us in and through the community gathered and the celebrant is celebrating with the people and leading prayers of the people. Then we got into lay ministry, lay people reading scriptures lay people leading the prayers, what it was, what it always was, that the liturgy was the work of the people and now it is expressed as the work of the people. I think that’s a good thing. I think it has empowered and has facilitated lay ministry in a new way and people are owning that new ministry. And that’s been good. But it was a long, hard, period to work through. Painful, for all of us, in various ways.

Barbara: You had several assistants while you were there. Wasn’t that one of things that came out of having assistants was that you were able to have an earlier service with the idea of being for young families with children.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, we had three services for a while. The middle service was called “the family service.” And that worked. When I didn’t have an assistant, three services on Sunday morning was hard to pull off and keep up with it all. And then as the church moved into the meaning of prayer book change, that meant persons of any age should be able to receive Communion, so the idea of children being in church to receive Communion if you had the two services we had, caused a big controversy over “I don’t want those noisy kids in my pew when I’m trying to hear the sermon.” By the way, in my old age, with hearing aids, I’m more sympathetic. But the problem was, what do you do with them? We finally worked that out, which I thought was a fairly satisfactory solution, and that was their having their own liturgy of the word in what’s now Faulkner Hall and joining us for the Communion part of the liturgy. And I think that finally worked out pretty good. We had a lot of hard times getting to that point and a lot of struggles to keep that going with people willing to volunteer to do something with the kids during that time that was more than babysitting, that was meaningful to really integrate them into living out some way with the scripture of the day and learning things about it.

Barbara: They no longer do that because. . . you know we had to stop for some reason having that extra service. Maybe it was budget, or something like that. But, now we have that extra service, but there is none of that back and forth, children either come for the whole service both nine o’clock and the eleven o’clock, and that seems to have worked out very well. Children also have an area at the front of the pews.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, I know they do, and I like that.

Barbara: And they encourage the children. . .

Reverend Sydnor: At the front is very key. One reason kids get irritated and act out at church is often that. parents hold them in the back where they can’t see what is happening and they get all distressed. I was sitting at St. Mary’s, Fleeton, VA, recently and in the congregation they have two or three families with kids. But one new mother was there with her crawling little child, who during the service, started crying and she put him down and he crawled up the aisle. And Sandi [the Reverend Sandi Mizirl] who is their priest, went down, called him by name and scooped him up her arms and finished the sermon with him in her arms; and when we got to the exchange of the peace, he was still in her arms. And she came down the aisle, and of course, it’s a small congregation, but he exchanged the peace with us as we exchanged the peace with her and him as well so he went back to his mom. She went to get the table ready for Communion. By that time, he’d crawled up again so she scooped him up in her arms and he actually stayed in her arms throughout the entire consecration. He had his little piece of wafer in her arms, then she had to hand him off to somebody so she could administer Communion, which she did. But it was just a lovely wonderful moment of saying well, he’s one of God’s children too and we’re glad he’s here. Now, I realize it’s a small congregation and you can do things you can’t do in other places, but was just really lovely.

Mac: Charles, I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t have been there when this happened because it was sometime when we had a substitute come in. Maybe you were on vacation or there was something going on but I think it was probably during your time, but we had as a substitute, an old retired minister that was living over Marlborough Point area that I’ve forgotten his name, but he was a nice old man.

Reverend Sydnor: Jack Beckwith?

Mac: Might have been. But anyhow he came and he was preaching his sermon and some little baby back in the back really tuned up. I mean he cut loose big and the minister, Jack Beckwith, or whoever it was, he persevered for a while, but the kid just didn’t let up and finally he just stopped, looked around and said, you know I’ve heard it said that the crying of a baby is more pleasing to the ears of the Lord than the snoring of saint. I think that’s one of the most cogent things I’ve ever heard.

Reverend Sydnor: I think I must have been there or at least I heard about what he said. I have quoted that. I think he was Randolph Crump Miller, a Christian educator, a writer in the Episcopal church [1910 – 2002].

Mac: Were you the one who said that?

Reverend Sydnor: No, no, I think it was Randolph Crump Miller who said that in a sermon. This whole issue, I remember, was a consequence of the prayer book change. What we discovered in prayer book change was, yes, for most of the history of the church, you were baptized and then you received the sacraments of the church. You did not have to be confirmed. That came along later when the church wanted to find a way to force people to move on to confirmation. Well if you can’t get the sacraments, some would say you are going to hell if you don’t receive the sacrament. So, you must go to confirmation class. But once we removed that requirement and said any baptized person can receive Communion then kids were, if you were serious about it, if you wanted kids in church to receive Communion, what do you do with them? The Rev. Dr. John Westerhoff [John H. Westerhoff, III, b. 1933, Episcopal theologian and author] used to say if children are unhappy in church, then change the church, not the children.

Barbara: Well I believe it was one of your assistants that we had our first female minister.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, Judy, Judy Burgess.

Barbara: Judy Fleming.

Reverend Sydnor: Judy Fleming and her married name is, I think, Burgess. Judy Fleming, yes. And she was, we should give her credit, she was very helpful in working with the Thurman Brisbane Center. She was very excited about that, in helping with that.

Barbara: Do you have anything to remark especially about any of your other assistants? Because you had Jack Souter and then Nathan Farrell. Did Joani Peacock come while you were there?

Reverend Sydnor: No, no, later.

Barbara: So, it was it was Jack Souter and Nathan Farrell.

Reverend Sydnor: The first was Ron Okrasinski.

Barbara: Yes, and wasn’t his ordination held at St. George’s?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, he came to us from the Roman Catholic tradition and was ordained in the Episcopal church with the service at St. George’s.

Barbara: He then went to Colonial Beach and now is retired.

Reverend Sydnor: And retired, yes.

Barbara: Yes.

Mac: He went to Colonial Beach?

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, he went to St. Mary’s [Episcopal] in Colonial Beach. In fact, recently he did some supply work for St. Mary’s, White Chapel, down here after Torrance Harmon retired before they hired somebody. You asked what I was going to say about each one of those persons. Each were very different. We had job descriptions. As time went on, more and more assistants were working, as I got older, with youth ministry, and young adults and kids. And that’s what happens. I mean, let’s face it, when you’re 55, you’re not as relevant to kids as you used to be, I don’t think, or you can work at it, but it’s harder so a lot of that took place. I don’t think I have any specific memories of saying something unique, except Jan Saylor’s professional lay ministry on our staff with our youth was excellent and she got them involved in the summer program of repairing houses for those in need. I’d like to be able to say something unique that each of those other persons brought to us and contributed but I’m not sure off the top of my head, I can name that. I think it’s refreshing to have different styles of preaching and sometimes that’s good and sometimes that’s bad, but it’s the way it is.

Beth: They had unique backgrounds. You had the first woman, yes? And you had someone who had been a lawyer.

Reverend Sydnor: That’s right.

Beth: And then you had someone who had been a Catholic priest.

Reverend Sydnor: Not a Catholic priest, but a Catholic deacon.

Beth: So you had quite a diversity.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes. I had come, as you know, as the first assistant that St. George’s ever had.

Barbara: You were the first. And when you came, I did want to ask you about this. The idea was that Christ [Episcopal] Church was just starting back up and you and Tom Faulkner would take turns going back to Christ Church to fill the pulpit.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, we were in charge of Christ Church at Spotsylvania Court House. And serving that community for services and pastoral care and all the rest, yes, we were.

Barbara: Until they got themselves in a financial situation to be on their own.

Reverend Sydnor: To be on their own.

Barbara: Did that last for a couple of years?

Reverend Sydnor: A couple of years, yes, it wasn’t too long.

Barbara: By the time you were called to be full-time.

Reverend Sydnor: Oh yes, they were on their own. We gave them land. . . some details get so fuzzy, but there was a piece of land which St. George’s owned, which had been the site of a chapel of which the foundation, a few bricks remained. It had been torn down, rotted down, many years ago and at some point we gave historic Christ Church the land for them to do what they wanted with it, to benefit for their own building campaign which they eventually did. It wasn’t immensely valuable; it was landlocked, as I recall it, at the time. I don’t know what happened after that. And there were some issues with title that had to get resolved but we finally did that for them. Part of which facilitated their getting on their feet. It wasn’t a lot of money, but it helped.

Barbara: Then later when our brass cross, our altar cross was stolen, they gave us a wooden cross made from some timbers of the . . .

Reverend Sydnor: The 1840 church.

Barbara: That as I recall was suspended from the chancel.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, it was suspended from the chancel ceiling.

Barbara: Which was something very different for us to have. Then we passed that on to a mission church, in Stafford

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, yes, since my time.

Barbara: But that mission church closed.

Reverend Sydnor: It didn’t make it

Barbara: And the cross went back to Christ Church.

Reverend Sydnor: Oh did it? I didn’t recall that.

Barbara: Gone back to Christ Church. In the mean while since we had the chancel change, with the reredos, there’s a cross on the reredos, since our table is now out front.

Reverend Sydnor: The arrangement today looks lovely. I like it very much. And I think you, Barbara, were on that committee that struggled with all of that. And The Rev. Bill Pregnall, [former Dean of our Church Divinity School of the Pacific] helped a lot in leading us through that thorny mess of trying to come a place where we could agree on some changes because there were all kinds of opinions.

Barbara: That’s right. First was the reredos, which had been taken down when the church was painted under Tom Faulkner and stored in the gallery.

Reverend Sydnor: And Marge Arnold, bless her heart, was determined to put it back up.

Barbara: And she wasn’t the only one. A bunch of us, because it was starting to be moved around when they were working in the gallery.

Reverend Sydnor: It was part of the historical fabric. Yes, it had a place.

Barbara: Brown Morton [Reverend W. Brown Morton, III] felt certain, that if it wasn’t with the original church it came after the fire because there was a door in it that went back to the vesting room, and now it’s probably more or less in the same place that it was.

Reverend Sydnor: Exactly.

Barbara: Now, if you said you were going to remove it would, they wouldn’t agree.

Reverend Sydnor: They wouldn’t do it now.

Barbara: Well there was one ceremony you had, I don’t know if you remember it, but you very much involved when the City of Fredericksburg appointed a committee for the celebration commemorating Washington, the bicentennial of his death. And we had a ceremony of the memorial service that was held a replica, we tried to, of what had been and it was very well attended with people from all walks of life and all of the churches. [December 12, 1999]

Mac: Was that the evening prayer?

Barbara: That was the evening prayer.

Mac: Out of the . . .

Reverend Sydnor: 1662 Prayer Book which would have been in use then.

Mac: 1662?

Reverend Sydnor: 1662, the big book, the prayer book.

Mac: I know I remember asking you, if George Washington had been there that night, would he have felt right at home? And you said yes.

Reverend Sydnor: Yes, yes.

Mac: It was exactly what he would have been used to.

Barbara: The only difference it was when you prayed for the nation, instead of the king, you prayed for the president.

Reverend Sydnor: We prayed for the president, the liturgy got a little bit updated.

Mac: What president was it then? [William Jefferson Clinton]

Reverend Sydnor: It was ’99,

Mac: It was Gerald Ford; it was early ’76.