By May, 1864, Julia Wheelock, a Union Relief Worker, describes the medical scene, after the three of the four Civil War battles that affected Fredericksburg: “All the public buildings—the Court-House, churches, hotels, warehouses, factories, the paper mill, theatre, school-buildings, stores, stables, many private residences— and, in fact, everything that could give shelter was converted into receptacles for the wounded, until Fredericksburg was one vast hospital.”

Brandy Station was the intended destination for Union wounded but the shift in plans by Grant moving south meant there would be a delay as the road system to Fredericksburg was poor The town had made no preparations for the influx of the wounded..

By that time there were more than 20,000 human wounded (four times the pre-Civil War population) had to be treated by 40 or 50 surgeons. The federal wounded, not often treated warmly by the city population. There were few necessities, such as beds, crutches and food ran low at one point in May 1864. The crisis went on for more than two weeks.

St. George’s functioned twice as a hospital, once after the December 13, 1862 battle and then again in May 1864 at the time of the Battle of the Wilderness. At the former, Fredericksburg was a primary care facility as field hospitals dealing with the wounds after the battle. Two years later it was an evacuation point with the hospitals functioning to sustain federal wounded until they could be transported back to Washington by train or boat.

In 1862, wounded fled the battlefield mainly along Hanover and George Street some carrying themselves, others by friends or wagons. The largest hospital was at St. George’s and was the brigade hospital for the famed Irish Brigade. Major General St. Clair Augustin Mulholland in his memoir of the Pa. 116th Regiment describes the scene in today’s Sydnor Hall:

““In the lecture room of the Episcopal church eight operating tables were in full blast, the floor was densely packed with men whose limbs were crushed, fractured and torn. Lying there in deep pools of blood, they waited very patiently, almost cheerfully, their turn to be treated ; there was no grumbling, no screaming, hardly a moan; many of the badly hurt were smiling and chatting, and one—who had both legs shot off—was cracking jokes with an officer who could not laugh at the humorous sallies, for his lower jaw was shot away. The cases here were nearly all capital, and amputation was almost always resorted to. Hands and feet, arms and legs were thrown under each table, and the sickening piles grew larger as the night progressed. The delicate limbs of the drummer boy fell along with the rough hand of the veteran in years, but all, every one, was brave and cheerful. Towards morning the conversation flagged, many dropped off to sleep before they could be attended to, and many of them never woke again.”

Another soldier walking on the sidewalk on the evening of December 13, 1862 noted the dead bodies piled on either side as high as the top step of church. On the fence around the cemetery there were belts, cartridge boxes canteens, and haversacks, tin cups with the bottom or side shot away, canteens minus the side.

Beginning on May 8, 1864, conditions were more desperate as the need increased. 10,000 to 15,000 Soldiers were evacuated from the Battle of the Wilderness into Fredericksburg for eventual evacuation. Fredericksburg soon became a “City of Hospitals”. Church pews were the first thing to go to accommodate the wounded. St. George’s was the only church whose pews survived since they were fixed, nailed down in place and not easily removed. However, pews left in Sydnor Hall which functioned as a chapel were removed. A federal quartermaster reported in Sydnor Hall

“The pews of the lecture room of this church were entirely torn out and used for coffins and bedsteads; the carpeting on the church and the cushions were used as bedding for the wounded and were otherwise destroyed. The blinds were taken to admit a free circulation of air through the church and were considerably broken thereby, some of them were burnt.

Upstairs the following scene was recorded by James Bowen in the History of the Thirty-Seventh Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers”

“In the Episcopal Church a nurse is bolstering up a wounded officer in the area behind the altar. Men are lying in the pews, on the seats, on the floor, on boards on the top of the pews. Two candles in the spacious building . throw their feeble rays into the dark recesses, faintly disclosing the recumbent forms. There is heavy, stifled breathing, as of constant effort to suppress involuntary cries extorted by the acutest pain. Hard it is to see them suffer and not be able to relieve them.”

Men tried to comfort themselves as best as possible in the Church:

“Passing a church occupied as a hospital, a night or so after our arrival, we hear the music of an organ. Entering the building, with every pew and aisle crowded with wounded, a ghostly light from a dozen lanterns making the darkness seem only the more horrible, we saw in the organ-loft a group of men with their arms in slings, one of whom, who had sustained a mere trifle of a hurt, was fondling the organ-keys. Presently, as we stood there in the pallid gloom, down from the gallery, and along the aisles, floated the tender notes of “Home, sweet Home,” sobbing, sighing, as with the unutterable longings of souls famished for glimpses of the dear spot, around which all of life’s joys and hopes are forever grouped.”

Charles Coffin in his book Four Years of Fighting reports that ultimately many did not survive as infections invaded wounded men

““There was the sound of the pick and spade in the churchyard, a heaving-up of new earth, — a digging of trenches, not for defence against the enemy, but for the last resting-place of departed heroes. There they lie, each wrapped in his blanket, the last bivouac! For them there is no more war, — no charges into the thick, leaden rain-drops, — no more hurrahs, no more cheering for the dear old flag!”

(13 bodies removed from our cemetery after the war)

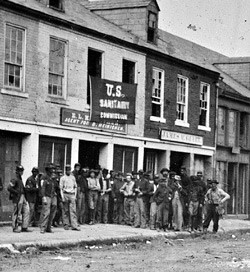

Aiding in the effort were up to 500 workers from two relief agencies, US Christian Commission and US Sanitary Commission , the latter housed on William Street (see close-up picture at the beginning of the article). Theirs was an uphill task As the latter commission reported in their Annals “With only a small corps of surgeons, almost entirely destitute of food and medical supplies, having but few men competent to act as nurses and attendants, their condition was pitiable and wretched in the extreme.” Food and other types of physical assistance were the primary tasks or the relief workers though many functioned as secretaries to inform relatives at home about their condition.

Clara Barton who served in the blocks surrounding St. George’s wrote.

Ms. Julia Wheelock reported providing chicken soup to men from either the Episcopal or Baptist Churches: “While distributing my crackers and soup to the inmates of a large church, where there are perhaps a hundred and fifty or two hundred poor sufferers lying side by side upon the floor, nearly all seriously and many mortally wounded, my ears were saluted with the voice of song, and, looking around to see from whom it came, I saw a poor fellow with a severe wound in both arms, whom some one had raised up from his hard bed. He was sitting on the floor and leaning against the wall, singing as cheerfully, and apparently as joyously as if he were seated at the social hearth with his own dear family. It was a scene which brought tears to my eyes, for the voices of song strangely mixed with the dying groans, and I thought that one who could shut his eyes to the scenes of distress around him, and so far forget his sufferings as to attune his heart and voice to singing, must indeed have experienced the blessedness of the Christian’s hope.”

After the occupation of Federal troops, St. George’s did make a $2,487 claim for “pews, cushions, and carpeting… alleged to have been appropriated by the United States for the benefit of its wounded soldiers.” In 1887, Congress passed the Tucker Act which included this claim. By 1905, after not receiving payment, the trustees of the Church filed a petition with the US Court of Claims. The case was heard and the court awarded the Church only $900 though only received $810 was received in 1916, fifty years after the original claim.