Beginning on the night of December 11, 1862 and continuing into the 12th, Fredericksburg suffered a level of destruction that had not been seen up to that time. After the event about $170,000 in donations came to the city to cover part of the losses or about $3.6 to $3.7 million in today’s dollars. Portions of the Army of Northern Virginia competed against each other for the level of support. This represented not only support but sympathy and understanding to the plight of the town. It was the first sacked city since the British burned Washington and was the first American city sacked by Americans.

The scene was ghastly from both the day of war and the actions that ensued. A member of the 34th New York wrote that “piles of dead” littered the street corners and “every doorstep was a tombstone” There were large gaping holes in many of the residences. Almost all citizens were gone except poorer whites and African Americans.

It could have been worse. An account from the London Times of January 23, 1863 follows which provides a mention of St. George’s: “The first impression of those who rode into its streets, and who had witnessed the deu d’enfer which the Federal guns had poured upon it for hours upon Thursday, the 11th of December, was surprise that more damage had not been done. But this is explained by the fact that the Federals confined themselves almost entirely to solid round shot, and that very few shells were discharged into the town. Nevertheless a more pitiable devastation and destruction of property would be difficult to conceive. Whole blocks of buildings have in many places been given to the flames. There is hardly a house through which at least one round-shot has not bored its way, and many are riddled through and through. The Baptist church is rent by a dozen great holes, while its neighbour, The Episcopalian Church, has escaped with one. Scarcely a spot can be found on the face of the houses which look toward the river which is not pockmarked by bullets. Everywhere the houses have been plundered from cellar to garret; all smaller articles of furniture carried off, all larger ones wantonly smashed. Not a drawer or chest but was forced open and ransacked. The streets were sprinkled with the remains of costly furniture dragged out of the houses in the direction of the pontoons stretched across the river. Many of the inhabitants clung to the town, and sheltered themselves during the shelling in cellars and basements.”

Order and discipline broke due to the level of the frustration the day before in the bombardment. Revenge was in the air furthered by alcohol. Men had broken into a wholesale store on Caroline Street with a stock of liquor. They opened the spigots, filled their campaigns and then left it on so to spill onto the street. As a member of the 13th New Hampshire wrote :

“Furniture of all sorts is strewn along the streets. Houses are ripped, battered an torn, windows smashed and chimneys thrown down. Every namable household utensil or article of furniture….. are scattered and smashed and thrown everywhere..” Personal property plummeted by $11 million or by 85% with slave values representing half of that figure.

Junior officers supervised the removal of food, blankets and bedding from homes but beyond that offered little control as soldiers totally wrecked some homes. The 15th Massachusetts infantry laid down 100 mattresses so the troops would not have to sleep in the mud. The total generals took the better homes for their residence.

Eugene Blackford, son of Mary Blackford, who lived on Caroline Street, wrote of both encountering his home and St. George’s. Note that the London Times was writing after the street battle on December 11 and Blackford is describing conditions after the main battle of the 13th: “You can’t imagine with what emotion I witnessed the ruins of our old home. It has been used by the Yankees as a hospital and there was a large pile or arms and legs lying under the cut-paper mulberry tree in the yard, and six of the scoundrels were buried the grass plot. The lot was strewn with books and papers and the whole house defaced. No fencing whatever remained about the premises, either in front or behind. In the steeple of the Episcopal Church alone I counted twenty cannon hole shots. Most were in the main building. Some houses have fifty to seventy holes in them. “

The justification of the Federals for their actions fell into three broad categories – enjoyment, retaliation and the nature of war. After a long series of battles of 1862, the stolen food was a treat and they lived better than at any time of the war. Many soldiers cited the stubborn resistance of Barksdale’s troops and their unconventional means of fighting. Fredericksburg became the first battle that drew civilians into the fray and was representative of how the character of war was changing. It was the source of resentment of Confederates for many years.

Individual St. George’s parishioners had suffered. Mayor Montgomery Slaughter’s home on the northeast corner of Princess Anne and Amelia (original building no longer standing) was described by a Northern journalist – “every room was perforated by shot and had been shattered by shells. The plastering, pulverized by the shock of the explosion, was thick upon the floors which, in turn, were ripped as if ploughshares has been driven through them. The mantle pieces were from the walls.” The Slaughters would move back but the damage is indicative of the state of Fredericksburg. Slaughter also headed a committee that collected 55 inventories from Fredericksburg citizen totaling $137,038 detailing property losses to determine how the funds would be distributed to its citizen. Interestingly enough no St. Georgians submitted property losses.

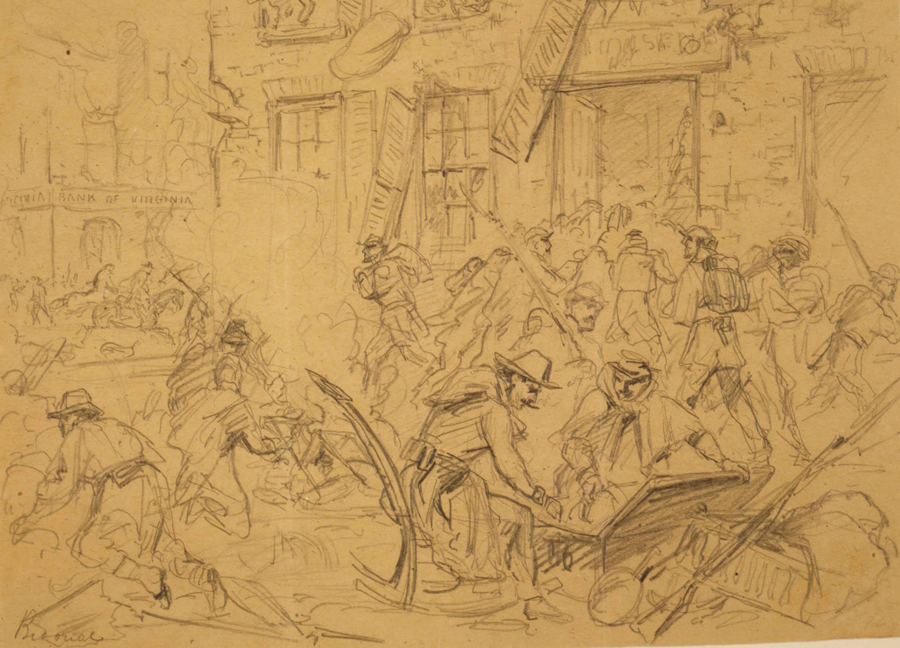

St. Georgian John Wallace’s home was located on the southeast corner of Caroline and William (no longer standing). The Wallace House and Store was two stories and twice the length of most business building. The family lived upstairs. Caroline Street suffered substantial burning as well as destruction of property. (See drawing at the beginning of this article). Wallace in a note to his cashier as the president of the Farmers Bank (National Bank building) was surprised that his house was not burned. “All the houses on the Va. Bank square and my square (including the Bank) were burnt except my house which much injured.” His son A W. Wallace, age 19 described the devastation “..nearly all the old furniture had been destroyed or stolen; a fine library, the accumulation of many years, had been wantonly torn up, the book leaves spread on the floor and mixed up with a paste made from the annual supply of flour.”

One other parishioner, John B. Ficklen, the proprietor of Belmont, had to keep affiliations private as he was pro-union. On one hand he appeared a well-to-do southerner who as a miller and banker also owned 27 slaves, most of whom were employed at his mills. However, he kept his intentions silent at the vote of secession and was able to sneak his sons through enemy lines to the North.

The most famous story of St. George’s during this time was one example of plundering, the stealing of communion silver donated by John Gray, a bookseller in Fredericksburg and warden who provided a 4 piece silver set consisting of 2 cups, flagon and paten in 1827. Initially federals entered the building and the sexton Washington Wright, a free black thought they were going to pray. However, after taking the silver, Wright was able to rescue one of the cups. Historian Carroll Quenzel provides an account of the rest of the story shown here in outline form and quoted from his book The History and Background of St George’s Episcopal Church, Fredericksburg, Virginia:

1866 -Paten

“Learning of the loss of most of the communion service, Mr. Ruxton Maury and Miss Ann Maury, both of New York, presented St. George’s with a new flagon and cup. In the spring of 1866 the vestry learned that the paten of the service was in the hands of the New York Police. Since this piece was easily identified by its inscription, presumably it was returned.”

1869-Plate

“According to the vestry minutes a portion of the communion service came into the possession of Mr. 0. E. Jones of Jamestown, Chautauqua County, New York. On behalf of the St. George’s vestry the Episcopal rector at Jamestown attempted to buy the plate but Mr. Jones declined, stating that he desired to present the service in person to the Church. On June 8, 1869, the vestry formally moved that since a considerable length of time has elapsed without it being convenient for Mr. Jones to personally return the plate, it “authorizes the Reverend Levi Norton and a Mr. John F. Kinney of Jamestown to thank Mr. Jones for his generous action and to receive the plate.”

1931- Cup

“On the other hand, a well-informed vestryman has written that a friend of St. George’s Church advised Mr. Reuben Thorn, the senior warden, that he had seen the goblet and waiter at a residence near Albany, New York, and supplied the name and address of the holder. At first this individual, who was a candidate for high public office, refused to surrender the property, but he returned the silver within a week after the wardens threatened to send the facts to the New York papers. Perhaps Mr. Jones was the politician mentioned by Judge Wallace but it would be unwise to be positive about the matter. In 1931 a resident of Wollaston, Massachusetts, offered to return a communion cup taken from the church during the Civil War for #75. The woman accepted the vestry’s counter-offer of #50 and the cup was replaced in the church as a memorial to the late Miss Betty Goodwin, for many years president of the chancel guild.”

This is not the end of the story – the silver was stolen twice afterwards. It was stolen in 1980 but then found shortly afterwards in a nearby alley. Approximately ten years later in April, 1990 it was stolen again after someone broke into the Church from the alley. A $500 reward was offered. As Rev Charles Sydnor said “It has actual value, sentimental value and historic value.” On April 5, it was found at the home of an 18 year old Woodbridge man who had the silver as well as items from Corky’s from downtown Fredericksburg.

Thus, from the time the silver was stolen in 1862 it took 69 years to get it back and it was still a target of thieves almost 60 years after that!