December 11, 1862 would directly bring St. George’s into the hostilities of the Civil War. It was that day that the Church became a fortress against an advancing Union line coming from Stafford. Located prominently on a hill overlooking key streets to the north, the Church provided a wonderful location for soldiers to view approaching advances and as a base to deploy forces against the Union. St. George’s played a role as Confederate stronghold late in the day. The delay created by the Confederates provided General Robert E. Lee time to consolidate his forces on Marye’s Heights for a battle to take place 2 days later. The hero of the day was General William Barksdale whose headquarters was at Market Square, today a part of the Fredericksburg Area Museum next door to St. George’s.

This day is not as well known as the main day of battle, December 13th but there were a number of firsts. The Federals on the 11th created the first bridgehead landing secured under fire. The unorthodox fighting by the Confederate forces hiding in homes and other shelters contributed to the first case of street fighting known in North America. This along with the Federal bombardment by just under 150 guns created destruction in Fredericksburg that would foreshadow on a smaller scale of World War II after the D Day invasion. Over 9,000 shells were lobbed in the city.

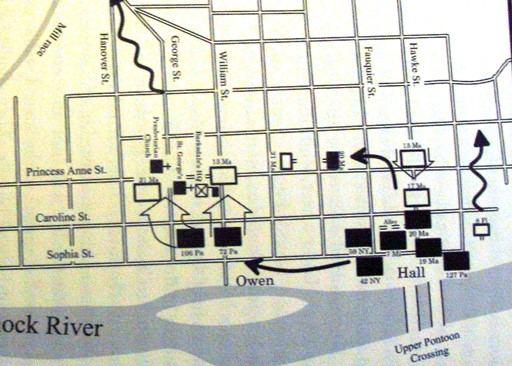

The map above from Frank O’Reilly’s excellent book on Fredericksburg shows that the action around St. George’s starting with one of 3 pontoon crossings, in this case the one at Hawke Street (“Upper Pontoon Crossing”) with severe fighting along Fauquier and Hawke (east to west location) and Sophia, Caroline and Princess Anne (north to south).

Fredericksburg’s defenders included approximately 16,000 men of Brigadier General William Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade deployed close to the river. With the threat of imminent combat, many of the town’s residents had previously evacuated their homes and fled to safety. By the day of battle, the Confederates had constructed rifle pits and knocked loopholes in river front homes. They fought in groups of 5 to 10 men that could move quickly. They depended on both speed and surprise to handle a much larger enemy.

The Union forces goal beginning after 5AM was to get across the river and move to confront the Confederates just west of town. The first strategy was the landing of engineers to construct the pontoon bridges. Fog hampered their task. Also, four elements from Col John Fiser’s 17th Mississippi reinforced by the 8th Florida provided the sniping that made their task all but impossible. When the Federal assault failed through devastating loss of life of key engineers, Henry Hunt of the Federal shifted strategy to establish a “beach head” by crossing the men over in boats and the artillery effectively to concentrate bridgeheads and drive CS underground. A ferocious Union bombardment began around 12:30pm with over 150 cannon line along Stafford Heights. After two hours between twenty-five and forty buildings were badly burned. Still, over the day, the Confederates had delayed the Federal crossing for 8 hours until approximately 2:30pm.

A Union artillerist describe a companion soldier’s attempt to destroy St. George’s clock:

“An officer of…[another] battery…remarked that the first shot he put into the city should pass through the clock; in fact, he proposed to breach the wail in such a way that the clock would fall’-into the body of the church. He explained that he felt impelled to this act though a sense of predestined responsibility….

As many guns as could be brought to bear opened upon the city with a murderous, deafening roar. Remembering the threat against the tower and clock…I watched through a glass for their destruction, but the hands still moved on….

Asking my friend…why he had failed in his threatened demolition…he replied that he watched the first shot he fired at it flying, as he thought, straight for the mark, but that before reaching the dial the shell visibly swerved to the right and only clipped a comer of the tower. The second shot was never aimed at the clock at all. He said he experienced such a change of feeling that nothing could have induced him to harm it,”

The heroes on the Federal side using this alternate strategy were the 7th Michigan. The crossing began shortly after 3 p.m. Under the cover of a heavy Union bombardment, two companies of the 7th Michigan readied boats along the Stafford shore. When the firing stopped, the soldiers dashed from their places of concealment along the riverbank, shoved the 31-foot-long pontoon boats into the water, and began rowing and poling. They arrived at the shore and were able to establish a skirmish line and after being reinforced by the 19th Massachusetts and captured 31 prisoners established a toehold on Sophia Street. The 20th Massachusetts was deployed on their right. The pontoon boats continued to ferry back and forth across the river with additional reinforcements, enabling Hall to solidify his grip on the town. Down river the middle pontoon, near city docks at 3PM federals were able to get across the river.

The Confederates were anything but through. Fiser’s 17th Mississippi had to fall back to Caroline and took up new positions in the backyards between Sophia and Caroline Street. They concentrated fire on head of Hawke Street and kept 7th Michigan from the crown of hill.

Fiser’s Confederates hid in attics, chamber, and cellars along the east side of Caroline Street. The confederates would conceal themselves in a cellar or attic, wait for the Union soldiers to pass, then shoot at them from the rear. Bullets seemed to come from all directions from an invisible foe. The Miss allowed the Federals enter the yards leading to Caroline street before they loosed volley in faces. Still, the 19th Mass and 7th Michigan were able to move to Caroline Fiser pulled back turning his left flank However, CS counterattacked on 19th Mass by the 13th Miss and drove them back towards the river.

The federals would be able to retake the lost ground by the valiant action of the 20th Mass after 4pm. At orders from Hall, the regiment, 307 strong, advanced down Hawke Street in a lengthy column that according to historian Donald Pfanz “had the appearance and function of a human battering ram.” While this happened, 19th Mass crept through the backyards to reclaim hold on Caroline. . They climbed fences, breaking into backdoors of houses. .

The massed body of men, hemmed in by houses on the left and right, made a perfect target for Barksdale’s soldiers. When the head of the regiment reached Caroline Street, the Confederates unleashed a torrent of fire that staggered the regiment and nearly annihilated the leading platoon. Nevertheless, the regiment pressed ahead.

The Confederates were gradually able to fall back as Barksdale aimed to consolidate his forces around Market Square. By now the pontoon bridges had been completed, and Hall’s remaining regiments charged across, extending the Union line as far south as William Street. At the same time, a second Union brigade crossed the Rappahannock at the lower end of town, at the modern city dock, and threatened to turn the Confederates’ flank.

By 6pm. the 21st Mississippi lay on parallel streets – one company held foot of William Street while another moved to George Street to right. A 3rd company held Sophia Street between them. The Confederates on higher ground on William Street had direct view of the approaching federals. Confederates had fired on the 20th Massachusetts which drew attention to them on William Street. The brief firefight occurred on William. Barksdale thought routed federals but they were only regrouping. Mississippians on William Street exposing those on Sophia

The 106th Pennsylvania led the Union advance south along Sophia Street toward the junction of Sophia Street and William Street, supported by the 72nd Pennsylvania and 42nd New York and surprised the Confederates. They moved to Caroline plunged into unsuspecting flank of. 21st Miss and trapped 21 prisoners and forced them to retire to Princess Anne Street. The action moved to St. George’s. As O’Reilly writes “Mississippians entered houses and fired from windows commanding William and George Street. Some of the Confederates took over Saint George’s Episcopal Church and probably the Presbyterian Church for a clear shot down George Street.”

With darkness stealing over the contested town, Barksdale decided that he had done enough. He ordered his men to fall back to the main Confederate line, located on Marye’s Heights. The Confederate main task had been successful but in an enormous cost to the town.