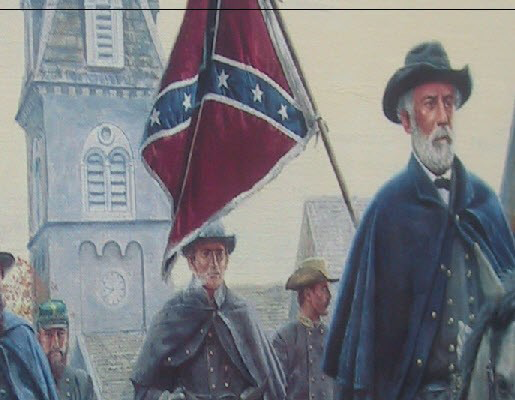

The writer, minister and abolitionist, Moncure Daniel Conway visited St. George’s as an 11 year old boy visiting one Christmas. This article is just the opposite – General Robert E. Lee, a man in the last 18 months of his life visiting St. George’s. Lee was 62 and suffering from a heart ailment but it did not interfere with his pace of life. (The painting at the left is a portion of “Lee at Fredericksburg” by Mort Kunstler depicting him riding down Princess Anne Street, November 20, 1862).

Lee’s reason for visiting St. George’s was as a delegate representing Grace Church, Latimer Parish, and Lexington at the 74th Annual Council of the Diocese of Virginia in late May, 1869. Then serving as president at Washington College (today Washington and Lee), Lee was a reluctant attendee. The end of the school year was close at hand and certainly he had many details to complete. Personally, there was a new house to complete. However, Lee was never one to decline a call for service and he accepted his election from Grace Church as a delegate.

Lee’s biographer Douglas S. Freeman describes Lee’s unusual arrival time and scene. “Although it was nearly midnight when his train arrived, the station was jammed, and as the moon was shining brightly, the people easily recognized the General. Instantly they raised the rebel yell as it had not been heard there since Sedgwick, in May, 1863, had been driven back across the Rappahannock.. the Veterans’ Band of the Thirtieth Virginia regiment — Corse’s brigade, Pickett’s division, the very name awakening echoes — turned out and serenaded him royally, before 1 o’clock. The General did not respond with a speech, after the way of politicians, but he sent out his thanks to the musicians, and Major Barton presented them with a bottle of something wherewith to console themselves for the General’s silence. It was noticeable that in the welcoming crowds the Negroes were as enthusiastic as Lee’s own veterans.”

Lee’s host was Thomas B. Barton and his son William Barton just across the street from St. George’s. Both were lawyers with significant real estate holdings and were members and pew holders. Thomas Barton was on the Vestry in 1866 and the oldest lawyer in Fredericksburg. There was a personal connection with Lee. One of Lee’s Lexington physicians in 1869 was Dr. Howard Thornton Barton, the son of Thomas Barton. He was a physician’s surgeon in the Civil war and set up a practice in Lexington after the war and was a member of Lee’s Church as well a suitor of Lee’s daughter Mildred. Dr. Barton was such a persistent visitor that Lee referred to Dr. Barton as “the last rose of summer.”

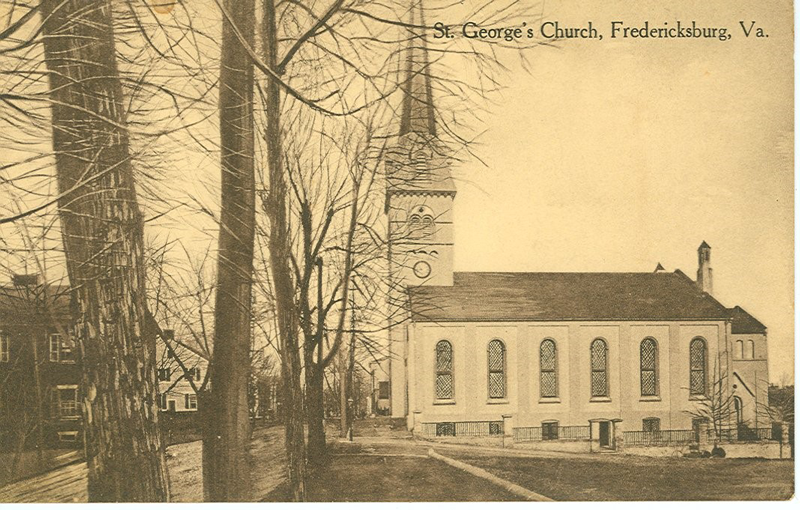

In 1905 the Barton house was torn down and the Princess Anne Hotel was erected in the location at 904 Princess Anne Street. Today it is an office building. We have an undated postcard from Tony Kent’s collection showing the Barton home probably at the turn of the century on the left side of an unpaved Princess Anne Street. It was an 18th century late Georgian home originally erected by James Maury. Note that St. George’s has diamond paned windows and no stained glass.

Lee was probably the greatest celebrity to visit the current Church building. A committee from the town came to the Barton residence and asked him to hold a reception at the Exchange Hotel. He declined saying his reason for coming to Fredericksburg was attend a religious meeting, the Annual Council which precluded personal appearances. Declining a town reception, however did not prevent people from coming to him and he sent word he would be glad to see any of his friends privately.

Lee remarked in a letter to his wife that “the town seems very full of strangers, and I have met many acquaintances.” He may have been referring to this description of one stranger in Freeman’s biography: “The whole town chuckled, however, at the performance of a new settler, a Northern man, who wanted to see General Lee and had his own ideas of etiquette. He did not know General Lee’s host and would not enter the Barton house unbidden, so he rode up with his wife and child and sent in a request that the General would “come out and see him.” Lee left the house, walked down to the street, and greeted the trio in the vehicle.”

John Goolrick in his history of Fredericksburg in 1922 has a wonderful description of the attention given to Lee:

“The Barton house was besieged by young and old, anxious to shake hands with him. The Bartons gave a large reception, and the writer recalls that scene as if it were yesterday.

“General Lee stood with Judge Barton and his stately wife; General Barton and his wife, and the peerless beauty, Mary Triplett, who was the niece of the Bartons. To describe General Lee would be superfluous. The majesty of his presence has been referred to. He inspired no awe or fear, but a feeling of admiration as if for a superior being. People who spoke to him turned away with a look of happiness, as if some long felt wish had been gratified. Toward the conclusion of the reception, when only a few intimate friends remained, some of the young girls ventured to ask for a kiss, which was given in fatherly fashion.” There were a 204 delegates at the Council – 124 clergy and 80 lay. Lee served on two committees in the meeting. There were a number of Standing Committees – Lee was chosen for the “State of the Church”. He also served on a committee involving clerical support. Freeman asserts Lee played no role in the actual debate. “He was not present at the session when the council debated the admission of delegates from a colored church, but he was understood to concur heartily in the decision that the representatives should be seated.”

The record of the council’s work at St. George’s is preserved in a 186 page report which provides a fascinating social history of the time. Concerns expressed in the meeting included “excessive ritualistic innovations” and in particular practices in worship not a part of the Book of Common Prayer. Actually, over a 1/3 of the document is composed of Parochial Reports, reporting Church statistics. St. George’s reported 256 communicants and a total of 186 in the Sunday School. After the meeting, Lee returned via Richland on the Potomac to pay a visit to his brother Sydney. It was his last visit as Sydney died two months later. He reached Lexington on the night of June 1 – just in time for final exams at Washington College. Lee never returned to St. George’s and died in October, 1870.