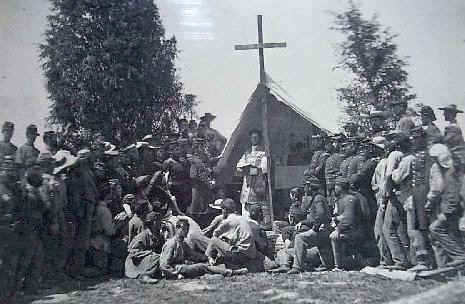

Church services had been a part of the both armies on Sunday. But after Antietam in September, 1862 more and more revivals were requested by the soldiers themselves and not necessarily from chaplains. Many troops also came from a revivalist background. Officers supported revivals since there was the belief that Christian soldiers made better soldiers.

What had changed ? Armies on both sides by the end of 1862 realized the war had reached a stalemate. While the Confederates were carrying the east they had lost key battles in the west, particularly in Tennessee. Even in the east their drive into Maryland had been checked at Antietam in September, 1862.

Death had become real, touching nearly every family and town. It was expected the horrible conflict would begin all over in 1863. The amount of destruction of Fredericksburg, and the number of casualties together with the lull of the fighting provided a time where religious impulses accelerated over the long winter. The war itself became the greatest challenge of faith especially after Fredericksburg.

Faith was an essential part of combat – the belief that the Lord would guide the men through the ordeal but also lead their side to ultimate victory. The most recent revival in 1857-1858 (“businessman’s revival”) arose in many cities and set the tone for those in the civil war – “ecumenical and lay in emphasis, affecting all classes and regions.” Ultimately revivalism was connected to the progress they were making in the war, giving them the will to encourage the fight.

For many soldiers, the effect of revivals was not to bring them the first time to faith nor to renew those who had fallen away, but rather to confirm and strengthen their previous resolve to lead a life that was pleasing to God. It helped convert many youth that had not taken Christianity seriously.

Camp conditions led to revivals, encouraged by chaplains. We have two classic Confederate chaplain memoirs – John William Jones and William W. Bennett that speak to these conditions. The latter noted that young men away from the influences of home easily fell prey to temptation. Bennett identified intemperance as the principal vice of the army, speculation and extortion as the leading sins of the Confederacy at large. Jones also cites speculation plus the presence of Confederate officers, who led the way in drunkenness, profanity, and gambling.

While Chaplains often directed the service in the fields, lay participation was essential. (There were never enough chaplains, especially Congress slashed their pay). Chaplains offered communion, baptized converts, visited the sick and buried the dead. They helped the men handle fear of death and cope with daily troubles (such as justifying destruction amid Biblical teachings). They were treated like regular soldiers but did not take up arms. In Fredericksburg, there were ample clergy to attend to the needs of soldiers in the formal church.

During the conflict, many authors have estimated that 100,000 to 150,000 soldiers were converted in the Confederate armies which was 10% of their forces. About 1/3, according to one contemporary author, had some affiliation with a Christian faith. Union converted was about 5% of their total forces.

Two groups supported the chaplains of both sides. The Christian Commission was organized in 1861 which employed just under 5,000 agents and distributed printed materials to soldier. The comparable southern organization was the Evangelical Tract Society which was organized in Petersburg.

Revivals occurred both in the field and where there were churches such as St. George’s. (No regular services had been held at St. George’s since the end of November, 1862, and they would not resume until December 2, 1864 in today’s Sydnor Hall.)

So what were the revivals like? Field chaplain Rev. J. D. Stiles noted they held three meetings a day – morning and afternoon prayer meeting and a “preaching service at night.” “Our sanctuary has always been crowded… Loud, animated singing always hailed our approach to the house of God…the entire altar could scarcely accommodate the supplicants.” An historian notes the revivals were more concerned with “results than with process” and “laying stress more on participation and practicality than on contemplation and speculation.” Generally revivals lasted a week. Another variety was the protracted meeting which were held nightly over a longer period of time.

William Bennett in A Narrative of the Great Revival Which Prevailed in the Southern Armies wrote about the growth of revivals during the winter months. The most famous one involved General Barksdale in March, 1863: “In the space of six weeks one hundred and sixty professed religion in Barksdale’s brigade, while scores of others were earnestly seeking salvation.”

William Jones reported in his memoir Christ in the Camp that revivals were started in the Presbyterian Church and the Methodist Church but soon their facilities could not accommodate the numbers which came day after day. St. George’s as the largest facility played a key role. From March 26, 1863:

“Last evening there were fully one hundred penitents at the altar. So great is the work, and so interested are the soldiers, that the M. E. Church South, has been found inadequate for the accommodation of the congregations, and the Episcopal church having been kindly tendered by its pastor. Rev. Mr. Randolph, who is now here, the services have been removed to that edifice, where devotions are held as often as three times a day. This work is widening and deepening, and, ere it closes, it may permeate the whole army of Northern Virginia, and bring forth fruits in the building up and strengthening, in a pure faith and a true Christianity, the best army the world ever saw.”

A description by one of the minister follows:

“Long before the appointed hour the spacious Episcopal church, kindly tendered for the purpose by its rector, is filled—nay, packed—to its utmost capacity—lower floor, galleries, aisles, chancel, pulpit-steps and vestibule—while hundreds turn disappointed away, unable to find even standing room. The great revival has begun, and this [Barksdale’s] brigade and all of the surrounding brigades are stirred with a desire to hear the Gospel, rarely equalled. Enter, if you can make your way through the crowd, and mingle with that vast congregation of worshippers. They do not spend their time while waiting for the coming of the preacher in idle gossip, or a listless staring a every new comer, but a clear voice strikes some familiar hymn…the whole congregation join in…and there arises a volume of sacred song that seems almost ready to take the roof off…. The song ceases, and one of the men leads in prayer….does not tell the Lord the news of the day, or recount to him the history of the country. He does not make “a stump-speech to the Lord” on the war—its causes, its progress, or its prospects. But, from the depths of a heart that feels its needs, he tells of present wants, asks for present blessings, and begs for the Holy Spirit….”

On the next day Bennett reports: “At 11 we assembled at the Episcopal church. On this occasion, perhaps, 1,500 were in attendance, mostly soldiers. Every grade, from private to Major-General, was represented. Rev. W. B. Owen, chaplain of the 12th Mississippi regiment conducted the services; his theme was prayer; his text, ‘ Men ought always to pray and not to faint.’”

The services continued at the Church until the end of May, 1863. By that time Jones estimated 500 in Barksdale’s command had accepted conversion.

Just before Chancellorsville Jones reported on the ecumenical nature of the revivals as held at St. George’s and emphasized that religion was a part of the soldiers’ preparation:

“A rich blessing had been poured upon the zealous labors of the Rev. Mr. Owen, Methodist chaplain in Barksdale’s Brigade. The Rev. Dr. Burrows, of the Baptist Church, Richmond, had just arrived, expecting to labor with him for some days. As I was to stay but one night, Dr. Burrows courteously insisted on my preaching. So we had a Presbyterian sermon, introduced by Baptist services, under the direction of a Methodist chaplain, in an Episcopal church! Was not that a beautiful solution of the vexed problem of Christian union ?

“The large edifice was crowded with soldiers. They filled the chancel, and covered the pulpit stairs. After the sermon, some fifty or sixty of them, 1 should think, came forward with soldierly promptness, at the invitation of the chaplain, for conversation and prayer. An inquiry-meeting is held for them every morning. At that time it had been attended by about one hundred persons….”A little before sunset I ascended the spire of the Episcopal church, which still gapes with many an honorable wound received as the tempest of shells swept over it. There I had a fine view of the Federal camp, the dress parade, the hills whitened as far as the eye could reach by their tents, the heights malignant with cannon menacing yet more wrath to this quiet old town, lately so rich in happy homes and pleasant citizens, in social refinement and elegant hospitality.

Ultimately, a soldier’s faith was challenged by men who died that were models of upright citizens. The latter would be cast as saints showing selfish devotion to duty. In the end, it would be another example of the mystery surrounding God’s purposes and his providence. Soldiers believed that only when working into conformity to God’s will could man be assured that God would order events for man’s eternal good. The surprising component of Civil War religion was the failure on both sides to acknowledge and deal with the issue of fratricide.

As a result of the battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, some saw that God was on the side of the South and were jubilant and grew more confident in the Confederacy. Other were concerned this was at best a sign of self-righteousness and worse confusing war with the God’s purposes. Still a more practical response was caution realizing that foreign troops were still occupying Virginia.

The wartime revivals may have propelled the churches into a new growth after the conflict was long over. Churches turned inward to bolster its own authority but at the same time tended to back away social reform for labor, poor and African-Americans. St. George’s membership rose from 290 in 1862 to 348 prior to the creation of Trinity Episcopal in 1877. At the same time by 1872 the Church had relegated African-Americans to the south part of the far gallery, creating an issue for the next century.